Culture

Sponging in the Bahamas

"By far the most important marine product of the Islands"

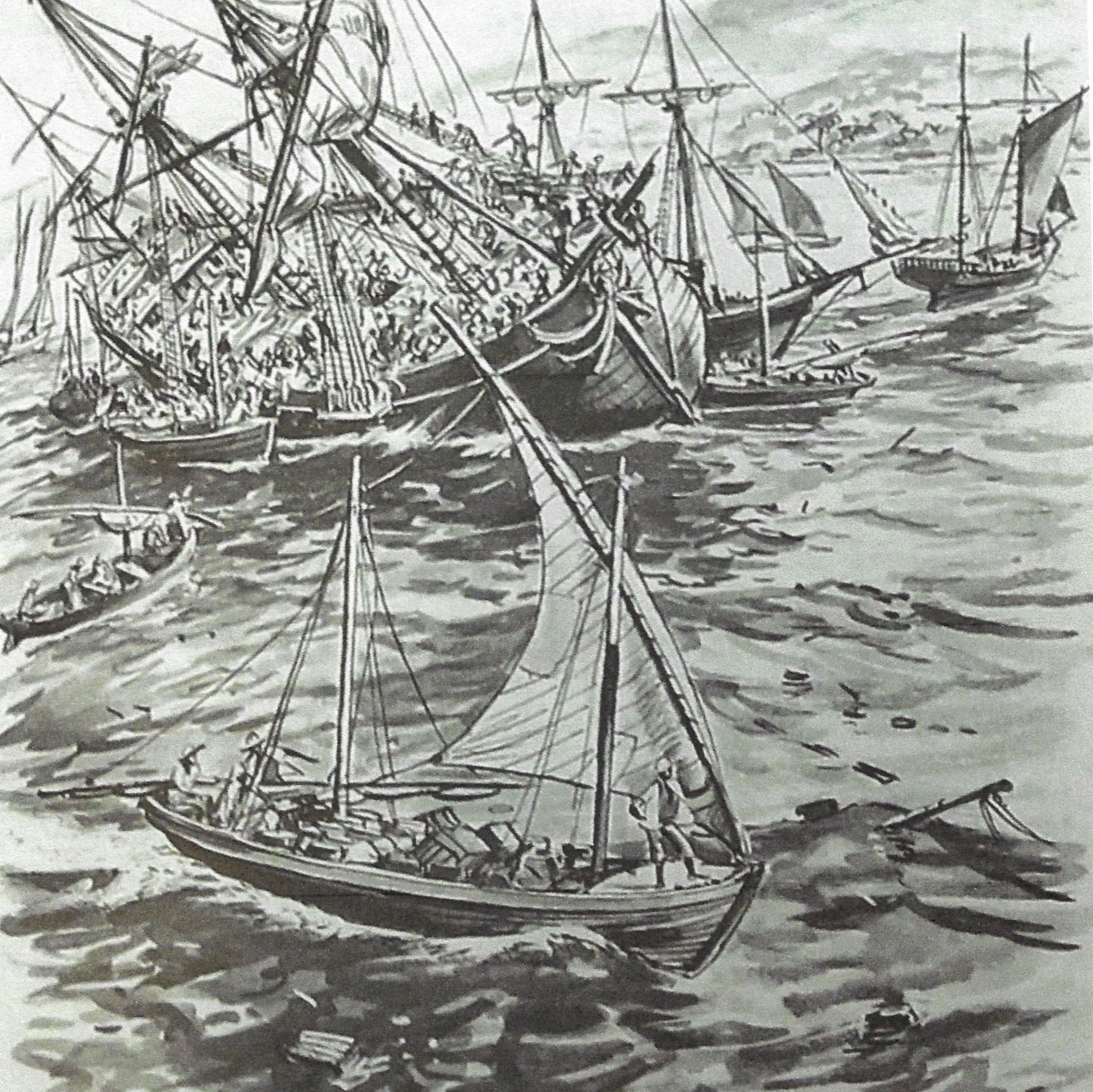

The sponging industry was once a leading industry in the Bahamas. At its peak, more than 600 vessels harvested sponges from the sea floor around the islands. In 1917, 1,010,239 pounds of sponges were exported, worth $400,578 (in 1917 dollars). This was due in a large part to World War I, which limited the Mediterranean sponge industry. More than a quarter of all sponges harvested in the world came from Bahamian waters that year. The Bahamas ranked as the third-largest producer of sponges around the globe in 1935.

The industry began when a shipwrecked French sailor, Gustave Renourd, began exporting sponges to Paris in 1841, and was later followed by his son-in-law, Edward Brown. When slavery was abolished in 1838, the sponge industry provided employment and income for former slaves and liberated Africans in the Bahamas.

At the London Fisheries Exhibition in 1883, Commissioner for the Bahamas A. J. Adderley reported that the Bahamas had a "brilliant assemblage of the ocean’s treasures that represent the fishing industries of the Bahama Islands." He said sponges were, “by far the most important marine product of the Bahama Islands.”

Fishing, Harvesting & Processing

Sea sponges are ocean animals with no central nervous system or brain. They attach and grow on hard surfaces such as rocks and coral. Their bodies are full of pores, with a dark elastic skin, which channels seawater through the body of the organism.

There are about 5,000 species of sponge in the world. The five types of commercial value in the Bahamas include the hardhead, grass, wool, reef, and yellow.

Harvesting is done by divers working from small boats using 10- to 12-foot poles tipped with iron cutting hooks or knives. A water glass, a bucket with a glass bottom, is used to locate and inspect the sponges. When the base of the sponge is left, it quickly regenerates. Regular harvesting actually enhances the health and population of the fishery by increasing population and removing older sponges. Cut sponges will re-grow within a few years, producing a bigger and healthier sponge than the original. Pieces of sponge broken off in harvesting will settle back to the ocean floor, reattach to a hard object, and regrow into completely new sponges.

Once cut, the divers gently squeeze the gray gelatinous substance between the sponge's skin and pores out of the sponge, called the gurry, and take them back to the larger boats.

Processed sponges are further cleaned, graded, trimmed and dried, and then sold and used for cleaning.

The End of an Era

Three hurricanes struck the Bahamas in 1926 in succession, disrupting and diminishing sponge populations. Overfishing also became a problem. The Agricultural and Marine Products Board Sponge Amendment Rules were created in 1937, which monitored fisheries and introduced a fishing season.

In 1938, a fungus killed almost all the prized sponge beds and the industry collapsed, putting thousands of Bahamians out of work. Until recent years, the sponge industry has been a fraction of what it once was in the islands.

See "Revival Of The Sponging Industry," from The Tribune, March 1, 2017

Also, "Sponging project moves into final phase as spongers ready to revitalize industry nationwide"," from the Bahamas Press, October 15, 2018

Sponging in the Bahamas, ca. 1891, a Scientific American article on Sponging from November 21, 1891

The sponge fisheries of the Bahamas cover a large extent of territory, give employment to about 6,000 men and boys, and are a source of revenue to the colony larger than any other industry pursued there… Sponges are always plenty at one place or another around these islands. They are always growing, and the supply is never short if they are sought in the right localities.

There is also always a lively demand for good sponges, and at prices that are not liable to change materially from year to year. The quantity shipped from these islands during the year 1890 was 623,317 pounds, the local value of which amounted to $31,500.

I have often asked this question: What becomes of all the sponges? The immense quantities sent from here seem more than enough to supply the world, yet outside of the sponge-producing region we see very few, if any, going to waste. Whatever becomes of them, the demand is about the same from year to year, the supply never fails, and prices maintain a very even scale.

There are about 550 schooners and sloops of from 5 to 20 tons and about 2,500 open boats engaged in the fisheries, giving constant employment to the 6,000 men and boys engaged. These employees are mostly natives of the islands, and follow this industry all their lives; in most instances commencing as boys, growing to manhood, and continuing at it as long as they are able to stand the fatigue and labor. Owners of sponge boats give a share of the proceeds of the sponge they obtain to the owners of the vessels for towing them to the sponging grounds and allowing them ship room. The sponge they obtain is kept separate from the ship's cargo.

Read More - Scientific American "The Sponge Fisheries of the Bahamas" Nov 21 1891

Methods

The method of obtaining the sponge from the sea bottom is by a staff and hook at the end, by which the sponge is torn from its place of attachment. At greater depths than can be reached by the hook, the sponger will sometimes dive for them, but this is seldom resorted to. The water glass is an indispensable article in locating the sponge on the sea bottom. It is a wooden cone with a glass set in one end and open at the other. It is about 18 inches long, and by placing the glass end just beneath the surface of the water and looking in the top, the operator has a clear view of the bottom of the sea, and with his staff in the hand not engaged in holding the water glass, he thrusts the staff down. When be sees and selects the sponge, he hooks it or tears it from its native bed.

"All its fine qualities are hidden."

The sponge, when taken from its resting place, has not the same appearance as when prepared for use. All its fine qualities are hidden. It is heavy, and contains a matrix of dark gelatinous matter with a dense external pellicle. This gelatinous substance is got rid of by maceration and washing, and the result is our well known companion of the bath.

On placing any of these forms of sponge, before cleaning, in a tub of salt water, and with the aid of a lens observing the central portion of the body of the sponge, one will notice something like a fine woven cobweb projecting from the central part outward, from which refuse matter may be seen issuing. Looking more attentively, an immense number of very small pores will be seen, through which the food, infusoria and other organisms, is taken. The more powerful the lens, the more wonderful the internal structure is shown to be, and the more surprising will the operations of nature in this particular case appear. With a powerful glass one can easily perceive the flagella or whips lashing the water, producing the inflowing and outflowing currents. Without the use of a magnifying power, the sponge would appear as a dead, inert mass.

Propagation of Sponges

The propagation of sponges, the method by which they increase, is not only interesting, but is certainly very curious. At certain periods there will be formed projections from the surface, yellowish-looking buds, which grow until they detach themselves, when they are driven out by the outward flow caused by the flagella or whips lashing at the water. These yellowish-looking buds then appear as helpless atoms of jelly. But this is not the case. These tiny germs or atoms have a motion that we would not suspect. With a lens we see the whole of these minute objects covered with minute cilia, which vibrate and propel it through the water until, arriving at sufficient distance from the place of its birth, it settles down on the bottom, loses its cilia and grows to become a sponge.

After the taking of the sponge from its native bed they are all sorted and the different kinds and grades separated. They must be trimmed or clipped, as it is termed, baled, pressed, and encased in canvas to ship.

"well worth visiting"

The sponging grounds of the Bahamas are well worth a visit. There is scarcely a more beautiful or interesting sight than a view in the clear limpid waters surrounding these sea-girthed islands on a warm day. The marine flora, the various forms of coral scattered in rich profusion at the depth of a few fathoms, is something marvelous for its varied and extreme beauty, and is not surpassed in any part of the globe.

In a tideway of medium flow it can be viewed to the best advantage. The graceful, undulating sea fans, with a variety of sea anemones, with the colors of the rainbow, the branching coral, some fashioned, one would almost believe, with human skill and artistic taste, with the most beautiful colored fish sportng in these fairy grottoes, the water being so transparent that the bottom can be distinctly seen at a depth of over 20 fathoms, all combine to make a vision which for beauty, novelty, and variety is very fascinating, and once seen will not easily be forgotten.

The local price of sponge ranges from 25 cents to $1.20 a pound, the fine wool sponge being the most expensive, while the yellow and glove sponges are the cheapest.