Culture

Folktales

Bahamian Folktales

The Rich Oral Tradition of Storytelling in the Islands

This section was gathered and edited by Cordell Thompson, local Exuma Historian and Director of the Pompey Center for Studies in Traditional Art, Music, Food and the Unresolved Mysteries. He credits The New York Times for much of his research.

Mr. Thompson served over 30 years with the Bahamas Ministry of Tourism. Among his many contributions, he concepted the long-running “It’s Better in the Bahamas” strategy and spearheaded development of The Bahamas Film Commission.

"The desire to know more about Bahamian folklore and storytelling has never left me. In fact, it becomes more and more of an obsession every day and I suspect it won’t stop until I feel I have recorded or experienced every story and its variant."

- Cordell Thompson

Origins of Bahamian Folklore & Storytelling

Detailed research into Bahamian folklore reveals an African germination and an American hybridization. Comparing the Bahamian folktales and those of other transplanted African tales in the New World, including Jamaica and America, to what might be the original version from Africa, has led to some fascinating and sometimes disturbing history.

The missionaries who assisted the colonization of Africa in the early and late 19th century went there convinced that the people of that “Dark Continent” could not possibly have any tradition or discipline that resembled “culture” in the sense that storytelling, poetry and dance represent a sense of the artistic nature of the civilizing process.

In his book, “African Folktales,” (Published 1970 by Princeton Press), Paul Radin noted,

“Many otherwise open-minded people find it difficult to believe that the Negro, of all aboriginal peoples, should preserve an oral literature of any artistic distinction which could be equated with our own folktales.”

The well-known German Africanist, Carl Meinhoft, (died 1944), in a paper, “An Introduction to the Study of African Languages,” relates, for instance, that when a collection of folktales from the Cameroons was published in Germany in 1887, many of the white people who lived in daily contact with the Africans for many years protested quite vigorously and indignantly and insisted that no “Negro” could possibly have composed them.

The vast body of African folktales were compiled by white missionaries who obviously set out to prove the primitiveness of non-Europeans. They totally disregarded the ancient civilizations of Egypt and Ethiopia that contributed so much to what later became Greek and Western philosophy.

We can also safely assume that African folktales were influenced by the religions of ancient Egypt with animal gods with human personalities. This influenced much of the African folktales despite the natural boundaries of deserts, mountains and rivers.

Fundamental to African folklore is the high degree of sophistication and the relevance to a contemporary scene as mankind works out his relationships with other people. The African storyteller took the approach of giving human characteristics in animal form to avoid insulting members of their same class or society to whom their story was intended to uplift.

Animal Figures

The most common animal figures in African folktales were the hare, or tortoise and the spider. According to Martha Warren Beckwith, in her book, “Jamaica Anansi Stories,” published in 1924, Anansi is a spider, the trickster hero among a group of animal figures. He was an important character of West Africa and Caribbean folklore.

In other parts of Africa, close to the Congo, the hare (Brer Rabbit) and tortoise are used in the folktales instead of the spider. The “Brer Rabbit” stories (best known through the Claude Remos tales in the middle and southern states of America) are found where a large population of enslaved Africans were from Guinea.

In what used to be called the West Indies, Jamaica, Barbados, etc., their main supply of folklore seems to have come from Upper Guinea, the Lower Niger (Ibo), Coramantie (Gold Coast and Ghana), Hausa, Mandingo, Nago (a Nangoe or Yoruba).

The exploits of the hare are found throughout the folklore of West Africa and they have the characteristics of failure and helplessness, but with cunning to outwit larger animals. These folktales can also be found in the African folktales in America.

Language Peculiarities

Collections of African stories were recorded during the height of Colonialism and were obviously missionary European language translations of the various African languages. Their structure resembles grammatical peculiarities that have now become known as black English or regional dialects. For example, the animals are distinguished as “Brer” or “Buh,” which is generally supposed to be “brother” or be an abbreviation of the word “brother,” but could probably be a title of great respect equal to “Mr.” It is curious to note that the Ashanti word “Nyam” to eat, is found in the Uncle Remus stories and some earlier Bahamian folktales. Jamaicans still use the word commonly to refer to eating.

I also thought Mama was the only person who used the term “day clean” to describe daybreak, an idiom obviously brought to the Bahamas by the Loyalist slaves at the end of the American Revolutionary War. The term is found in Uncle Remus, The Folklore of the Old Plantation, collected by Joel Chandler Harris in the 1880s. In the Bahamas, before alarm clocks were common, daybreak would be announced at the period when “fust fowl crow,” and second and third and so on. Sharp citizens would be up at “fust fowl crow” and the more slothful would wait for the third and fourth call. It was part of Mama’s vocabulary. When I learnt how to read and write, Mama would look at my exercise book and call figures, “fowl scratch,” In America, some writing that is hard to read may be called, “chicken scratch,”

Deep & Rich Folktale Traditions

The Bahamas is recognized as having one of the largest collections of folktales in this part of the world and has interested anthropology, sociology and other students of folk history since the middle of the 19th century and reveals much about European/white American fascination with African-transplanted cultures.

One of my favorite researchers of Bahamian folktales is Zora Neal Hurston, a major African American literary figure of the 1920’s Harlem Renaissance. She was an author and anthropologist who conducted several field trips to the Bahamas. Mrs. Hurston’s research was patronized by Elsie Cleo Parson, a white philanthropist and sociologist who conducted her own research throughout the Bahamas, visiting the remotest of Bahamian communities on her private yacht.

Click here to see and hear some of the Bahamian stories and dance songs as recorded/documented by Zora Neal Hurston, and obtained from the “American Folklore Society” in collaboration with the “Journal of American Folklore.”

Remembrance by Cordell Thompson

My fascination with folktales began through my grandmother, Martha Oliver, who was born in the small village of Mastic Point on the island of Andros. Mastic Point had once enjoyed a heyday as one of the major centers for the sponge industry. The sponge, a marine animal, was harvested, dried and used extensively in major industries around the world because of its absorbent properties. It was also used for felt hats and even padding for brassieres. At its height, the sponge industry employed over 3,000 Bahamians who harvested the product, mainly on the west side of Andros using Bahamian-made slops and dinghies. The sponge industry lasted until 1934, when a mysterious blight destroyed the sponge beds.

My grandmother was born in the 1890s and lived in Mastic Point when the sponge trade was flourishing. She was of African heritage with traceable roots to a group of Seminole Indians who had migrated from Florida to the West Coast of Andros in the 1820s. In more than one way she was a beautiful woman, with sharp features, copper-brown skin and long silky hair.

My grandfather, Captain Freddy Smith, hailed from George Town, Exuma. He was a descendent from Loyalists who arrived in the Bahamas at the end of the American Revolutionary War and were granted large plots of land in Exuma and throughout the Bahamas. My grandfather was a sponge fisherman and outfitter. An outfitter was a businessperson who would grant credit to the fishermen who were sponge fishing.

My grandmother and grandfather had seven children. I was born in 1944 and lived with my grandmother until I was about 7 or 8 years old. I had two elder brothers and two male cousins who also lived with my grandmother and we all called her “Mama.” All of our parents had migrated to Florida during World War II to fill jobs in farms and factories vacated by Americans called into military service.

To this day I believe Mama had deep spiritual and mystical powers. She used to “tell” or interpret other people’s dreams and she could also dream “straight” herself, that is, if she had an ominous dream about a certain person, the best thing that person could do was probably stay in bed all day. She was an accomplished herbalist. She knew every beneficial herb and bush, their uses and efficacy on different ailments. There is a family history of her curing kidney stones in my grandfather; common ailments such as colds, worms, nervous headaches, and women ailments were small stuff to her. She knew exactly what to boil and what doses to prescribe. I don’t believe she was unique in this field, not in those days when proper health care was hard to find, and it could be expensive. She was just one of those extraordinary Bahamians who knew intuitively the folklore and traditions of her people which were in many ways deeply rooted in Africa.

To me she was a magical person. She, like every true Bahamian, believed in “spirits” that could do you harm or do you good. She had a brother we used to call Uncle Josey who could play the guitar better than Joseph Spence. It is said my uncle learned his art naked in the graveyard at 12:00 midnight. Mama accepted the presence of “obeah” or witchcraft, although she never practiced it. She was too spiritual, deeply religious and attended both the Anglican and the Pentecostal churches with equal vigor and punctuality.

I tell my children the reason I don’t go to church now is because I had enough church for two lifetimes. And Mama could pray! Just after “dark shet in” or dusk, she would get dressed for bed, salve her head with alcohol, wrap her hair and get down on her knees in front of her four-poster bed. She would ask God’s blessings on the whole world, the President of the United States, King George, all the relatives who were in the States and pray about all their circumstances. I estimate the shortest prayer took about 20 minutes. It was a ritual you had to endure if you expected the old stories, that was the real payoff!

Mama Knew Every Story

Old stories are the Bahamas catch-all for the folktales, spirit tales, riddles, proverbs and even Biblical stories that make up the Bahamian oral traditions. Storytelling was the Bahamian way of passing on values while teaching and entertaining.

I believe Mama knew every single last story. I cannot ever remember being bored, and even though I might have thought I recognized one or two in a new telling, she always knew how to add a new element of surprise or wonder. Mama would tell these stories every night, propped up on her pillow until she or us, me, my brothers and cousins fell asleep. Sometimes Mama would be joined by other older relatives and the storytelling sessions would become even more engaging and competitive with other storytellers telling the leader, that it don’t go, or “taint so.”

At communal storytelling sessions, most stories would begin: “Once upon a time, a merry good time, the monkey chew tobacco and spit white lime. The cockroach jump from bank to bank, his tree quarter pitch never touch water.”

Most informal storytellers like my Mama would introduce their stories: “Dis time, one time.” Most stories would end: “Be bo bend, I’ll never tell a lie like that again.”

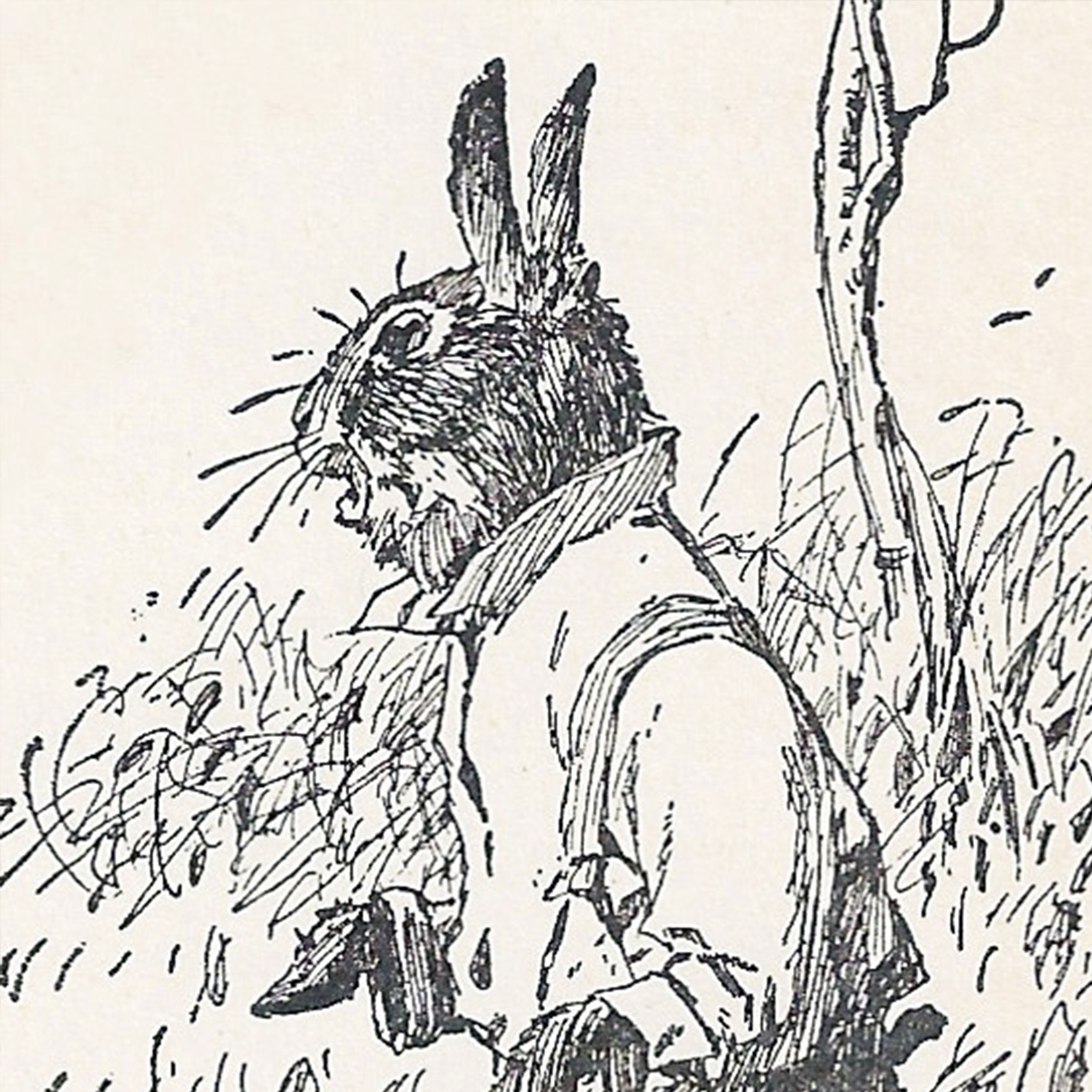

B’Bookie & B’Rabbie

The most popular theme in Bahamian old stories are adventures of B’Bookie and B’Rabbie. In our imagination, B’Rabbie is a slickster in rabbit form and B’Bookie is a silly goat and the constant and hapless victim of B’Rabbie’s cunning. B’Bookie is always being outsmarted and getting the short end of the stick, but they remain confidants and partners.

The B’Bookie and B’Rabbie relationship has come to describe many aspects of social relationships in the Bahamas. For example, if someone suspects a friend or associate is playing with the truth, he would tell the offender: “Boy don’t play B’Bookie and B’Rabbie with me,” or “If you is B’Bookie, I ain’t no B’Rabbie.” Politicians are often accused of playing B’Bookie and B’Rabbie with the voters.

Click here to read Journal of Caribbean Literature – B’Rabby as a “True-True Bahamian”: Rabbyism as Bahmian Ethos and Worldview in the Bahamas’ Folk Tradition and the Works of Strachan and Glinton-Meicholas by Virgil Henry Storr

My Favorite Stories Told by Mama