Wrecking in the Bahamas

Feb. 01, 2024

“Wracking – n. salvaging goods from a wrecked ship: 1788 Some call it “going a raking”: from “to rake,” searching for something with diligence and care; others “going a wracking” from “wrack” a foundered ship.”

Dictionary of Bahamian English, 1982

STRATEGICALLY LOCATED GATEWAY

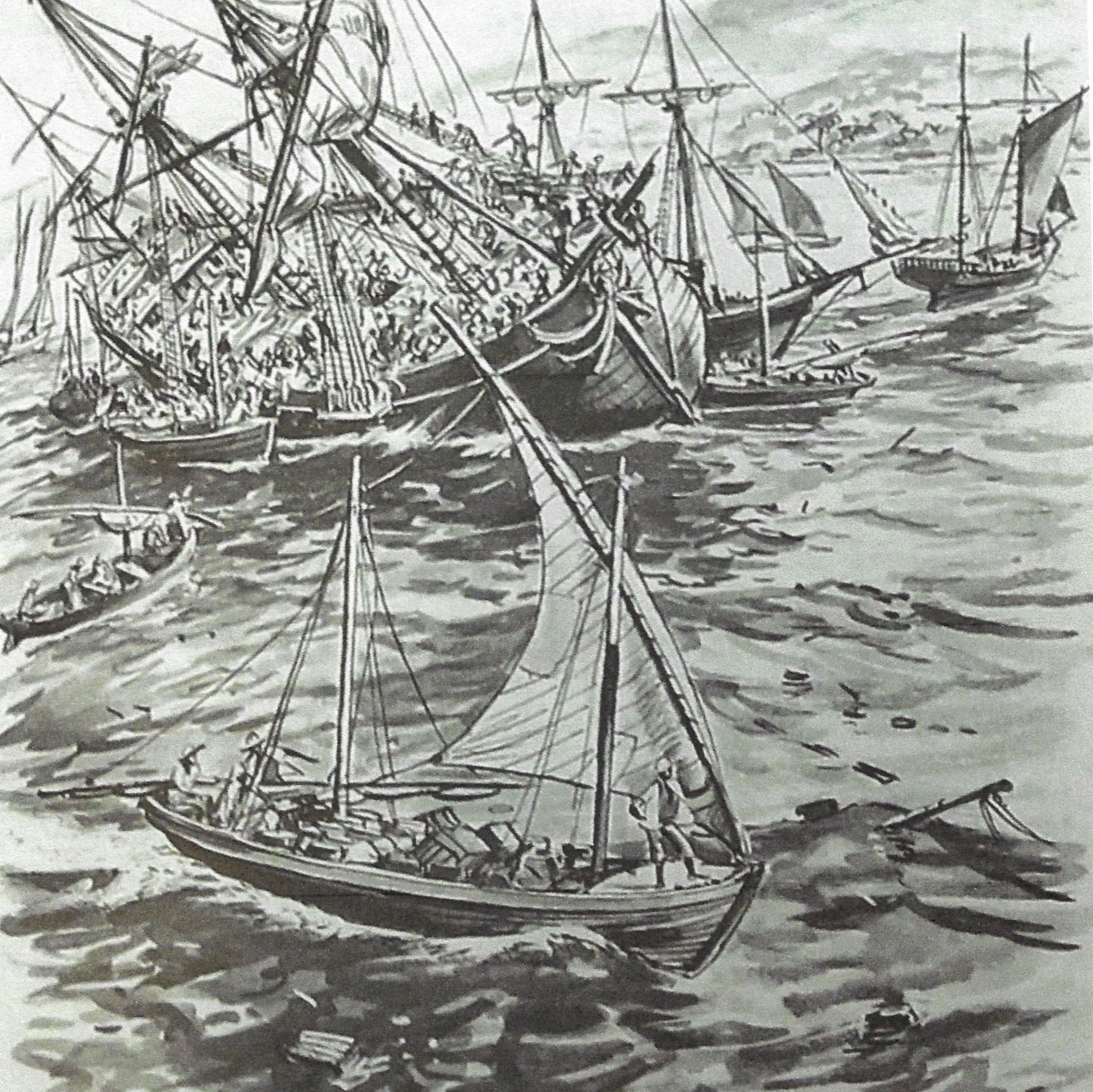

The Bahamas, a chain of islands with many uncharted banks and cays, form a barrier between the Atlantic Ocean, the Florida Straits, the Windward Passage and the Caribbean Sea. Ships under sail transiting this area in search of the riches of the Western Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America encountered the uncertain conditions of northeastern winds, hurricanes, unpredictable currents and shifting sandbanks throughout their transit. These unpredictable conditions, along with lack of navigational tools and inaccurate charts, conspired to drive many vessels onto the windward coasts of North Eleuthera, Harbour Island, Abacos, Bimini Cays and the west end of Grand Bahama (Lawlor & Lawlor, 2008).

WRECKING TO SURVIVE

The practice of luring foreign ships to wreck on reefs or shoals with the intent of plundering began with the first settlers, the Eleutheran Adventurers, a company of religious dissidents from Bermuda. Religious restraint soon gave way to the necessity for plunder as a means of survival. Primarily farmers and seamen, the ‘Adventurers’ began migrating to New Providence in the 1660s, attracted by ambergris, wrecks, and salt.

Though the practice of wrecking has been documented “as early as 1684 when marauders began establishing themselves throughout the Bahamas,” (Horner, Ship Wreck) wrecking as a profession became a cornerstone of the Bahamian economy through much of the 18th and 19th centuries.

So important was seaborne commerce through Bahamas that in 1846 2,000 ships passed Abaco Light. It was not until 1865 that it was discovered that a British Admiralty Chart which showed the reefs of the Little Bahama Bank, was inaccurate. The reefs were shown too far north of Walker’s Cay Reef and there was a difference of 5 degrees latitude and 4 minutes longitude for the Man-O’-War Cay anchorage, Pelican Cay, Little Harbour Cay, Whale Cay and Green Turtle Cay. This navigational blunder plus winds and currents hampered sailing ships’ ability to keep on course and off the rocks. (CO 23/181/29, Captain W. H. Stewart from Lighthouse Yacht Georgina to Governor Rawson, 6th October 1865).

A REGULATED INDUSTRY

Though the British colonial government ended piracy with the governorship of Woodes Rogers in 1718, a constant battle continued with efforts to exert control over the wrecking industry. In order for the government to assess duty and fees it progressively tightened salvage laws to include official licenses. Each member of a wrecking ship’s crew had to be licensed with the size of crews fixed according to the tonnage of a vessel. Salvaged goods, ranging from gold and silver, metals, rope, building supplies, livestock, foodstuffs, clothing to wines and liquors were to be transported to Nassau, where they were consigned to an agent. The government assessed 15% customs duty prior to the goods going to auction. Values assigned to wrecked goods varied widely with such factors as the difficulty of the salvaging operation affecting the final assessed value.

The owner of a salvaged vessel usually received one-third of the assigned value of the auctioned salvaged goods, with the captain and crew dividing the balance. The average annual income of an ordinary seaman on a wrecker was about £20.

The captain of the first ship to reach a wreck was considered the “wreck master.” The master had the authority to direct the salvage and was to make every effort to preserve life and property (Bahamas Handbook, Dupuch,1956).

The increase of wrecking provided a significant boost to shipbuilding and related industries. Between 1855-1864, 26 sloops “purposely built for wrecking,” averaging 47 tons each, were completed at Harbour Island, Eleuthera. (Lawlor, Harbour Island Story)

In 1856, there were 302 ships and 2,679 men, out of a total population of 27,000, were licensed as wreckers.

In 1850 the total imports for the Bahamas were valued at £92,756; imports from wrecked goods were valued at £16,786 or 18% of total imports. By 1852, the total imports were valued at £139,563 and imports from wrecked goods were valued at £46,515 or 33% of total imports (Lawlor & Lawlor, Harbour Island Story, p. 173)

WRECKING IN THE AGE OF AMERICAN EXPANSION AND CIVIL WAR

By the early 1820’s the city of New Orleans became an important transshipment point. Goods such as cotton, sugar, molasses, and tobacco were shipped via steamboat to the port where they were loaded on ships bound for Europe and to the cities of the northern eastern seaboard. The American expansion west continued the increase of trade, along with increasing opportunity for wreckers, on the sea route through the Bahamas (Lawlor, 2021

The American Civil War, 1861-1865, reduced the amount of shipping and wrecking activity, though blockade-running flourished. In 1865, £28,000 worth of salvaged goods were taken to Nassau. In 1866, the value of salvaged goods reached £108,000, and peaked at £154,000 in 1870.

The average profit from a wreck was estimated to be $11,000, and in 1865 Bimini inhabitants were said to be “entirely engaged in the occupation of wrecking.”

WRECKERS TO THE RESCUE

On 28 July 1816, a Spanish slave ship became stranded off Green Turtle Cay, Abaco. Wreckers rescued the crew and 300 captives destined for the slave trade in Cuba. Since Britian had passed the Slave Trade Act of 1807, any slave ship caught or wrecked within the borders of The Bahamas entitled those intended to be enslaved an automatic status of liberation. A British ship, Bermuda, brought those rescued to Nassau where they were indentured prior to their emancipation.

In the mid-19th-century impoverished Europeans, fleeing famine and disease, sought to emigrate to America often suffering the dangerous conditions of poorly built ships with lack of provisioning. In the 1850’s four immigrant ships were wrecked in the Bahamas.

In February 1851, the Cato, under the command of Captain Robinson sailed from Liverpool on a five-week crossing of the Atlantic. She safely traversed the Northwest Providence Channel but struck the Moselle Shoal near the Bimini Islands. Bahamian wreckers rescued 300 emigrants, taking them to Nassau where the “charitable and humane conduct of the white portion of the inhabitants.... [and] the negro portion came forward one and all with offerings of bread” (CO23/138/131, Governor Gregory to Earl Grey, 14th April 1851)

The one hundred and thirty German and French immigrants of the Ovando were rescued and stranded in Nassau without food or shelter. Governor Gregory ordered that they be accommodated in the military barracks. Crown Funds were used to send the emigrants to America. (Co23/140/254, Governor Gregory to Sir John Pakington, 7th December 1852)

In 1853, a fleet of wrecking schooners rescued over 200 Irish and English passengers of the Osborne off Grand Bahama. The schooners took all of the emigrants to Nassau, where they were put on a ship bound for New Orleans.

Bahamian wrecking ships Oracle and Contest came to the aid of passengers aboard the William and Mary after it hit Little Isaacs Rock, transporting them to Nassau over an eight day period. (Lawlor)

The Committee of the National Life-Boat Institution:

Voted...the silver medal to Mr. Robt. Sands (a man of colour) master of the schooner Oracle, of Nassau, New Providence, West Indies for his gallant services to passengers, consisting of 160 persons of the ship William and Mary of Bath, State of Maine, which struck on one of the coral reefs off the Bahama Islands. (CO 24/26/98, Chalmers Papers: Letter from Lord Newcastle 30th July 1853, and “Meetings of the Committee,” 1854, p.77)

The wreckers and boat builders of Abaco were praised by Governor Gregory in 1852, in a letter summing up the importance of not only the construction of the vessels but the humanity and skill of wrecking crews:

The wrecking vessels are a fine class of sailing schooners, many of them beautiful models, the most superior of them built at Green Turtle Cay, Abaco, where the genius of the people is manifested in their shipbuilding, the timbers being principally of native cedar or horse flesh mahogany of a very durable nature and the planking of a beautifully grained yellow pine from North Carolina, one of the southern states of America. The wrecking business is conducted on the whole very creditably, and these vessels and their hardy crews skilled in diving in deep water are the means of saving annually much valuable property from vessels stranded on various reefs, shoals and coasts of the numerous Bahama group besides no inconsiderable number of valuable lives. (Gregory to John Pakington, 7th Dec. 1852)

Wrecking on the Decline

Bahamians who are really interested in the future prosperity of their Islands would do well to prepare the way for the abolition of the present system of wrecking. Its evil influences are becoming more marked and more widely extended every day, and if it be not crushed, it will eat up all the life and industry of the Colony. As long as wrecking is a more profitable employment than agriculture, it is folly to suppose that people will abandon it except under legal prohibition.

New York Times, June 30, 1861

The construction of 37 Imperial Light Service lighthouses across The Bahamas and the charting of shoals and reefs contributed to the decline in wrecking as a profession. With the advent of steam power, ships could stay in the Gulf Stream and avoid the shallows of the Bahamas banks.

Modern, legal wrecking still exists and is called contract salvage, either pure or partial. Eventually tugboats – many of them from large US and later European tug and barge fleets such as Merritt Chapman & Scott, were used. Wrecks continued, but the process of recovering people and goods and ships became more logistical and engineering-focused, requiring fewer people, and fewer Bahamians.

The last major Bahamian wrecking operation was reported in 1905, when 77 small vessels and 500 men salvaged cargo from the steamer Alicia. The salvage award was US $17,690.

The last local, old-school Bahamian wrecking operation company was purchased by a New York company in 1920. U.S. Federal Courts, which have jurisdiction over maritime the way British Courts in Admiralty adjudicate colonial and British maritime law, closed their book of wrecking licenses the following year.

With thanks to the contributions of Eric Wiberg for his extensive knowledge and sources.