Culture

Bush Medicine

Efforts to Save a Vanishing Tradition for Modern Times

Among traditional cultures, ancient wisdom about medicinal plants is slipping away. In the Bahamas, the most experienced practitioners of plant medicine are in their 70s, 80s, and 90s. These elders are the last living repositories of bush medicine, and their wisdom is held within an increasingly fragile state.

Much of the information in print is often taken out of cultural and historical context, and lacks specifics such as scientific names, methods of preparation, dosages, length of treatment, locations of plants, descriptions of plants, and their indicated uses. As memories fade and infirmities of old age take their toll, this wisdom disappears from Bahamian culture, person by person, island by island, year by year. It's as if living libraries are burning down all over the Bahamas.

Plant Medicine in the Bahamas

Bahamian bush medicine is an innovative system of plant medicine unique to this region. It's more than a medicinal tradition: it's invested with utilitarian and spiritual values that were born of necessity, hardship and curiosity.

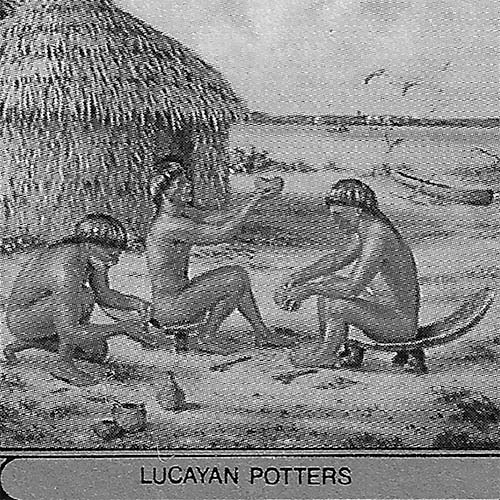

During the era of slavery in the Bahamas, enslaved people endured extreme hardships. Yet, they somehow managed to retain and consolidate a diversity of beliefs and practices from their African medical traditions. New arrivals retained an ancient wisdom about the ability to read medicinal characteristics of plants in the New World. They came with certain cultural and cognitive tools such as medicinal plant literacy, folk taxonomy and a tradition of using sensory methods for exploring new medicinal plants. Some used “other ways of knowing,” like dreams, to discover what plants could be useful medicinally. They were also exposed to European plant medicine through plantation owners. In a few cases, slaves were brought from plantations in the United States where some had also been exposed to Native American medicine.

A Proud Trademark of Bahamian Culture

Over time, these varied medicinal belief systems were changed by the new social, political, economic, religious and biological environment in the Bahamas. Their diversity of beliefs and practices were distilled and simplified so that a common thread evolved that runs through the Bahamian ethno-medicinal system—a focus on the here and now, on practicality, and the resolution of everyday medical complaints. They developed a system of medicine that is innovative, unique and effective in many ways.

Within a remarkably short three centuries, the development of bush medicine became an impressive accomplishment. It became a trademark of Bahamian culture and a tradition of which Bahamians should be proud.

Precious Knowledge at Risk

As a result of a cultural shift driven by the influence of modern medicine, and the dissolution of bonds between elders and the younger generation, members of the younger generation are rapidly losing interest in learning what the local bush medicine practitioner knows. They are lured away by the attractions and distractions of the modern world, while at the same time separating themselves culturally, spiritually, and pragmatically from several centuries of Bahamian plant knowledge.

In the process they lose more than valuable knowledge—they lose their cultural and spiritual traditions, and their connections with the land that help preserve ecosystems.

Bush medicine is a “place-based medicine,” meaning it's based on a healthy, ongoing, balanced ecological relationship between practitioners and the land where they harvest and use the plants. Place-based medicine is not static. It must be continually refreshed and renewed through the harmonious interactions of people, plants and place. It requires stable, healthy ecosystems, habitat not fragmented by development, and rising seas. When this is no longer possible, documentation becomes essential and urgent. The time for documentation is now.

Principles & Practices of Bush Medicine

The great majority of bush medicines taken internally are prepared as teas (steeped leaves, stems or roots) or as decoctions (plant matter boiled to release medicinal ingredients).

In order for it to be effective, many Bahamian residents believe that bush medicine must be prepared using an odd-numbered combination of plants, typically 3, 5, 7, or more. The preference for using an odd-numbered combination of ingredients is a hallmark of Bahamian bush medicine. Sometimes treatment time is also specified as an odd number of days, otherwise the treatment continues until the condition resolves.

A Language of Terms

Since Neolithic times, traditional healers have used a simple and effective language to describe in experiential terms the nature of plant remedies. They have used qualitative terms that are sensory; for example, terms such as heat, cold, dry, moist, excess, weakness, strengthening, etc. These qualities can have aspects that may include odor, color, taste, texture, and temperature. These terms are used both to express a condition of the patient, as well as some property of the plant that can be used to heal the patient.

Examples of Bush Medicine

The most esteemed plant used in bush medicine is aloe (Aloe vera), which is used alone or in combination for many ailments, both internal and external. As bush medicine practitioner Bertram Forbes stated: “Oh, that aloe, I tell you the truth, that’s the boss [plant].” A close second is gum elemi (Bursera simaruba) used by itself or in many combinations. “Ooh! That’s the best bush in the world!”

There are several hundred plants used on various islands in the Bahamas for bush medicine, as well as some non-botanical remedies used alone or in combination, such as urine, lye water, lard, rusted iron, and wood ash.

Wood ash has an alkalizing effect that may help with extraction of certain medicinal phytochemicals and is rich in minerals which may support healing.

A Unique Treatment for Tuberculosis

One of the most remarkable treatments recorded is for tuberculosis, which uses 7 ingredients, a combination of 6 plants and a cross of rusty iron in the bottom of the pot. One of the plants inhibits coughs, another inhibits the growth of the tuberculosis bacterium (Mycobacterium tuberculosis), and the rusty iron releases iron which in large amounts is extremely toxic to the bacterium. The 4 other plants have a specific effect or contribute to the synergistic effects of the medicine. One of the interesting questions is how this system of medicine evolved.

Practitioner Portraits

Bertram Forbes is well-known as a former practitioner of bush medicine on San Salvador Island. Born in 1934, he started learning bush medicine by the age of 5 when his mother sent him out to collect bush medicine plants. By 14 or 15, his mother began referring other people to him for treatment. He learned bush medicine from his mother, family members and highly respected midwives. He worked at the Gerace Research Centre on San Salvador from 1981 through 2008 as a gardener and groundskeeper. There he's remembered by generations of students, teachers and researchers to whom he had given bush medicine tours. Surprisingly, no one had recorded his knowledge until 2011 with Bush Medicine of the Bahamas.

Jeffrey Holt McCormack, Ph.D., author of Bush Medicine of the Bahamas, first met Bertram Forbes in 2007:

"He looked younger than his 73 years. He was energetic, spry, and eager to talk about bush medicine. He carried himself tall and erect; always acted like a gentleman, polite and respectful, yet spirited and animated, especially when telling his favorite bush medicine stories to visiting students. Over the years he honed his delivery of these stories for maximum effect. I never once saw him without a machete in hand which he has handled with skill, since learning to use it at age five. Now retired, he is no longer available for tours or treatments, though he leaves a lasting legacy for his service and contributions to bush medicine."

Sophia Pratt (1894 – 1997) of San Salvador Island is one of the most respected midwives in the Bahamas. She had a wide breadth and depth of bush medicine knowledge and possessed a skillful ability to diagnose and cure illnesses. She would travel around the island on horseback for a week or two at a time with her birth bundle and other travel essentials tending to newborns and their mothers, while administering bush medicines to children and adults.

She was so revered on San Salvador and the Bahamas that the Bahamian government flew her to Nassau where she was twice awarded commendations from the Bahamian government.