History

A Wilderness Tamed

In the Beginning

For most of its history, Grand Bahama was the “forgotten island” of the Bahamas. The most northern island of the Bahamas chain together with neighboring Abaco, the large island lost its indigenous population of Lucayan Indians at the beginning of the 16th century to slave raids by Spanish colonizers. The Lucayans were the first inhabitants of the Americas encountered by explorer Christopher Columbus in 1492.

Ponce de Leon & First Settlements

When Ponce de Leon reached Grand Bahama in 1513, he found just one old woman (“La Vieja”). She was taken away by the explorer as a guide to the Bahamas. It was de Leon who gave the archipelago its name, calling the Little Bahama Bank “bajamar” meaning “shallow sea” (“baha-mar” in Spanish).

Lacking any kind of suitable harbor, the island was not formally occupied again until the 19th century, although pirates, wreckers, blockade runners (during the America Civil War) and lumbermen made occasional forays there over the centuries.

In 1806, 500 acres of land at the west end of the island were granted to Joseph Smith, and the first official settlement was established.1

“…poorest, most isolated, neglected and hopeless…”

Settlers were poor black families who made precarious livings at the periphery of the Bahamas on land unwanted by anyone else. As Michael Craton and Gail Saunders observed, “Unquestionably, the poorest, most isolated, neglected and hopeless settlements were found in the all-Black islands or areas such as … Grand Bahama.”2

The pattern of struggling subsistence and colonial neglect continued into the mid 20th century, despite a brief flourish of prosperity during America’s Prohibition era, followed by a series of promising but doomed attempts at development.

Crown Land Grant Settlements

The first significant inhabitation of Grand Bahama, after some isolated earlier attempts, was by free blacks and former slaves (slavery in the British Empire ceased in 1834) who came to live on Crown Land grants.

They established a chain of small settlements along the southerly shore, with the most important at West End and Eight Mile Rock. The sea provided them a precarious living. In 1858, Thomas Harvey found some agriculture, horses and cattle on the island. The primary trade, besides salvaging wrecked vessels, was the harvesting of turtles whose flesh was salted and sold like beef in Nassau. There was only a single school and a couple of churches on the isolated island.

Read more: Grand Bahama in 1858 - from Thos. Chapman Harvey, Esq. Official Reports of the Out Islands of the Bahamas

Grand Bahama in 1864

Governor Rawson W. Rawson made the first full survey of the colony in 1864, in which Grand Bahama is mentioned only in passing. He found the island’s population in 1861 to be 858, but noted that many inhabitants were emigrating to Nassau, North Bimini, and other cays, “where the soil is grateful and remunerative”.

Grand Bahama included, he said, an island of 275,200 acres, 39 cays, and 24 rocks. It was 430 square miles in area, 66 miles long, and 11 miles wide at the greatest extent – figures vary in estimation in subsequent descriptions. There was one magistrate and two second-class constables to oversee the population, but little crime. The one school in Eight Mile Rock was attended by 19 boys and 14 girls. Besides a little agriculture, the main sources of income came from sponge production and wrecking, which provided two-fifths of the Bahamas’ “imports” and welcome customs revenue in the 1860s. In 1864, ten wrecks were salvaged on Grand Bahama and 31 on Abaco.

Settlements & Land Grants

Politically, Grand Bahama and the Berry Islands were in the Andros district, with two representatives selected by an electorate of 541voters. Rawson’s comments on the system of land grants helps explain the pattern of settlements, and why family names were often applied to the small villages. Each head of family was entitled to 40 acres, and for every other member of his family, adult or infant, slave or free, 20 additional acres.

Before 1833, grants of considerable extent were issued with annual quit rents. These were often not paid, so that on Grand Bahama 1,668 acres had reverted to the Crown. After that, Crown Land grants were sold by auction with “upset” (minimum) prices such as 10 shillings per acre after 1857.

“…the majority of grants are now of 20 to 50 acres. From 1844 to 1864 there appear to have been only four applications for grants of more than 100 acres, and one of 1,000 acres, the latter being of forest land in Abaco.”3

In 1949, Commissioner Pyfrom added a historical note about grants to his annual report:

“Grand Bahama was first settled by a few Loyalists in 1787. The Grants, Feasters, Heilds and Wilchcombes were the first settlers. The Wilchcombes made their homes at Settlement Point, West End; the Grants at Eight Mile Rock and environs; the Heilds at Free Town and the Feasters at Sweeting’s Cay. These loyalists married manumitted slaves and so in addition to the descendants of African origin; the present inhabitants include a large percentage of mixed Creole and African parentage. Land was granted to the inhabitants and their descendants during the year 1847 is still in their possession except for a large area at Settlement Point, West End, sold to the Butlin (Bahamas) Ltd.”

Historian Peter Barratt notes there were no grants recorded before 1806, save a sale of 200 acres in 1792.4

1887 to 1925

When Louis Powles, a Circuit Justice in the British colonial judiciary visited Grand Bahama in November 1887, he found the population had shrunk to about 700 persons. He said of his host and the island:

“Joseph E. Adderley, an African gentleman, who is both magistrate and schoolmaster—a combination not uncommon in the smaller settlements. He owned a great deal of land, and keeps a number of cows of a small but pretty breed. This is almost the only island where the people now own cattle in any quantity, but they complain that the price they fetch in Nassau is so low that it does not pay to rear them.”5

Read more: Grand Bahama in 1887

By 1908, there were three schools on the island, which had increased to 10 by 1925. Commissioner Saunders complained in 1918 that boys were pressured by their parents to leave school at age 14 (or before) and take up sponging, which he though injurious to both their educational and physical development.

Read more: Commissioner's Report - 1908

Mail Boats & Sponging

The usual way to get to and from Grand Bahama was by mail boat out of Nassau, stopping first in Abaco. A voyage took Amelia Defries five days (three without meals) in 1917. Her impression of the island folk was positive: “The Grand Bahama people are noted for their honesty and are as clean as in extreme poverty they can be.”6 On her return voyage on the Income, she was accompanied by two cows and a pig on deck destined for the market in Nassau.

Read more: Grand Bahama in 1917 - The Sponge Fishers - In a Forgotten Colony by Amelia Defries

Before the sponge beds suffered a catastrophic fungal blight in 1938, sponge was the primary export cargo, besides lesser amounts of agricultural products. The mail service was not always satisfactory or reliable, especially during the smuggling boom during America’s Prohibition era, as Island Commissioner Smith reported in 1925:

“The Mail Schooner ‘Emerald’ [Thomas Wilchcombe, captain] made 12 return trips to Nassau, the 13th being made by the M.V. ‘Cruiser.’ An additional Mail was dispatched by the Sloop ‘Sydney’ and an additional mail was received by the M.V. ‘Christina.’ The ‘Emerald’ has rendered extremely poor service: she has been irregular in her sailings when there was no excuse of weather: she has frequently failed to stop at all the stations on the route: she refuses freight constantly in Nassau, due to being already laden with liquor for West End. Furthermore, the Captain and crew are very unreliable and discourteous. If it is impossible for this District to have fortnightly mail service, the existing contract for a monthly service might at least be rigidly enforced.”

Read more: Grand Bahama in 1924

Read more: Grand Bahama in 1926

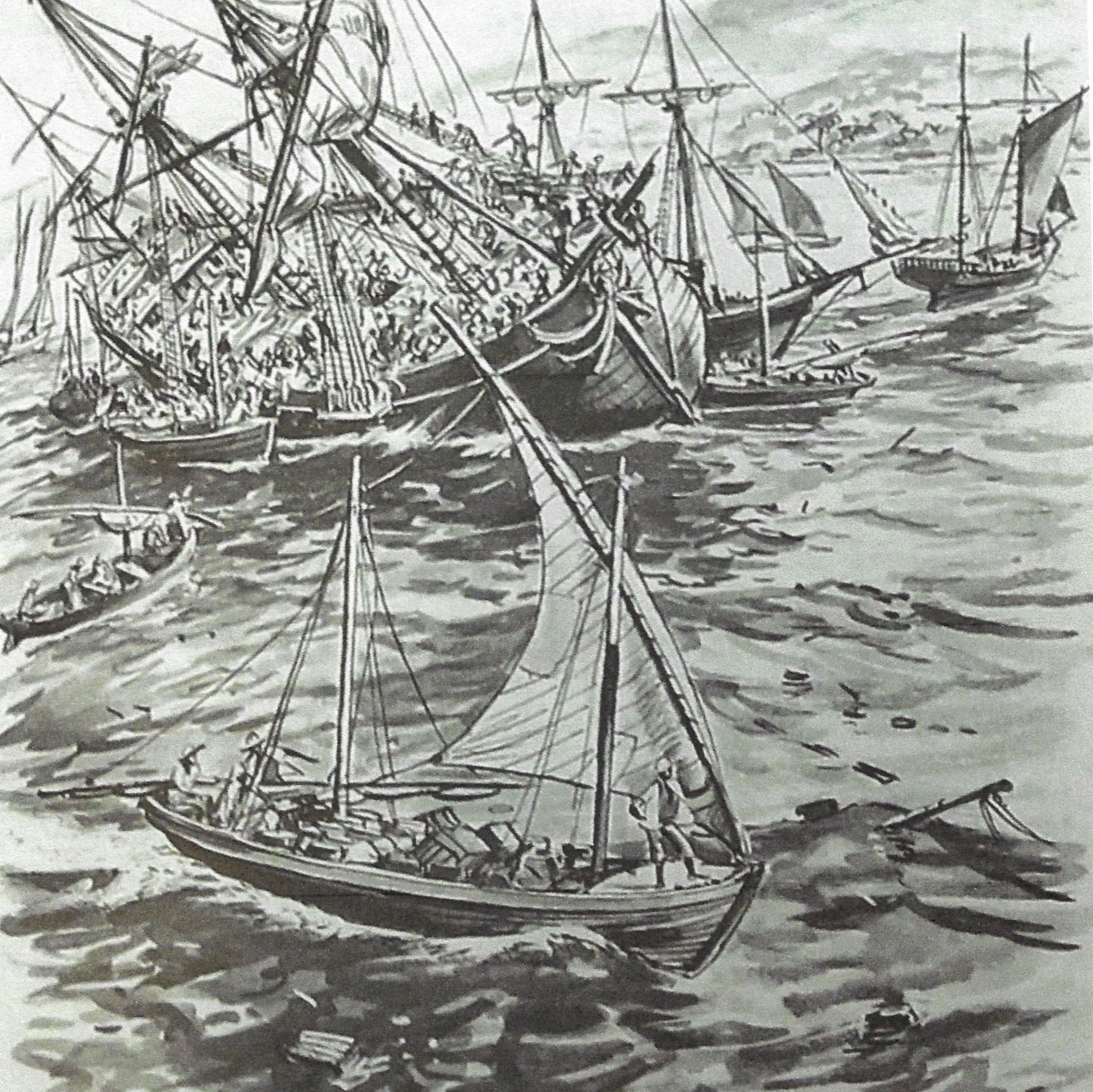

Exports During Prohibition

Merchant vessels also visited the island, both from Nassau and from foreign ports, especially during Prohibition when liquor cargoes from Nassau were transshipped via West End. Shipping increased from under a hundred vessels in 1908 to over a thousand in 1925 following the passage of the Volstead Act (“Prohibition”) in 1919, but receded again after Prohibition ceased in 1934.

1939 to 1949: Still Primitive & Rustic

Another lucrative export was "crawfish" or spiny lobster, especially while Axel Wenner-Gren's Grand Bahama Packing Company, Ltd. (later Sea Foods Ltd.), a fish and lobster canning factory, was in operation at West End from 1939 to 1945. The island population was 1,695 in 1921.

Commissioner Pyfrom reported in 1949 that “[t]here are twenty-two settlements within a radius of 83 miles with Settlement Point at extreme West End and Sweeting’s Cay lying to East. Conditions prevailing in most of the settlements are primitive and rustic.” Principal settlements in 1949 were:

| Settlement Point, West End | 1,590 |

| Eight Mile Rock | 360 |

| Pinder's Point | 141 |

| Hunters | n.a. |

| Pine Ridge | 900 |

| (Brady or Braudie Point) | 134 |

| Smith's Point | n.a. |

| Free Town | 82 |

| Water Cay | 248 |

| High Rock | 190 |

| McCleans Town | 134 |

| Sweeting’s Cay | 160 |

| Total Population | 4,104 |

Potential Is Noticed

Grand Bahama’s potential was noticed by a number of overseas observers in the early 1900s. An ambitious development proposal was made by Grand Bahama Mercantile and Development Company, an Anglo-American corporation whose representatives, Capt. G. Jordahn and the Honorable Frederick Guest, M.P., visited West End in 1925. Jordahn returned the following year with a Colonel Brinkman, who was also a representative of the East Palm Beach Land and Development Co. The Grand Bahama Development Company leased, “430 square miles of Grand Bahama, on grandiose promises to build a network of roads and a deep-water port at West End. Nothing came of this scheme, though it foreshadowed the development of Freeport-Lucaya…”7

In 1934, Major H. MacLachlan Bell “met a little man whose pockets were as full of blueprints as his head was full of plans. ‘Palm Beach sixty miles away – cheap liquor here – only twenty minutes by aeroplane; how about building a Casino and drawing the Palm Beachers who wish for a real exclusiveness?’”8

British holiday camp magnate, Sir William Butlin, who began a tremendously popular and successful chain of vacation resorts in England in 1936, set his sights on Grand Bahama in 1946.

1The Real Grand Bahama

2Michael Craton and Gail Saunders. Islanders in the Stream. Volume Two From the Ending of Slavery to the Twenty-First Century. Athens: University of Georgia, 1998, p. 158.

3Governor Rawson. Report on The Bahamas for the Year 1864. London: H.M.S.O, 1866, pp.3 3-34.

4Peter Barratt. Grand Bahama. London: Macmillan, 1989, pp. 44, 49.

5L. D. Powles. Land of the Pink Pearl. London: Simpson, Low, 1888, p. 58.

6Amelia Defries. In a Forgotten Colony. Nassau: The Guardian Office, 1917, p. 29.

7Craton and Saunders, Op. Cit., p. 246.

8H. MacLachlan Bell. Bahamas: Isles of June. New York: Robert M. McBride & co., p. 130.