History

Wallace Groves’ Island "Free-Port"

Abaco Lumber owner Wallace Groves was quite aware of the challenges involved, and had long mulled over possible solutions, arriving at one of breathtaking complexity and scope. He would propose a privately-owned and developed “free port” industrial complex to the Bahamian government and its British overlords.

History of Free Ports

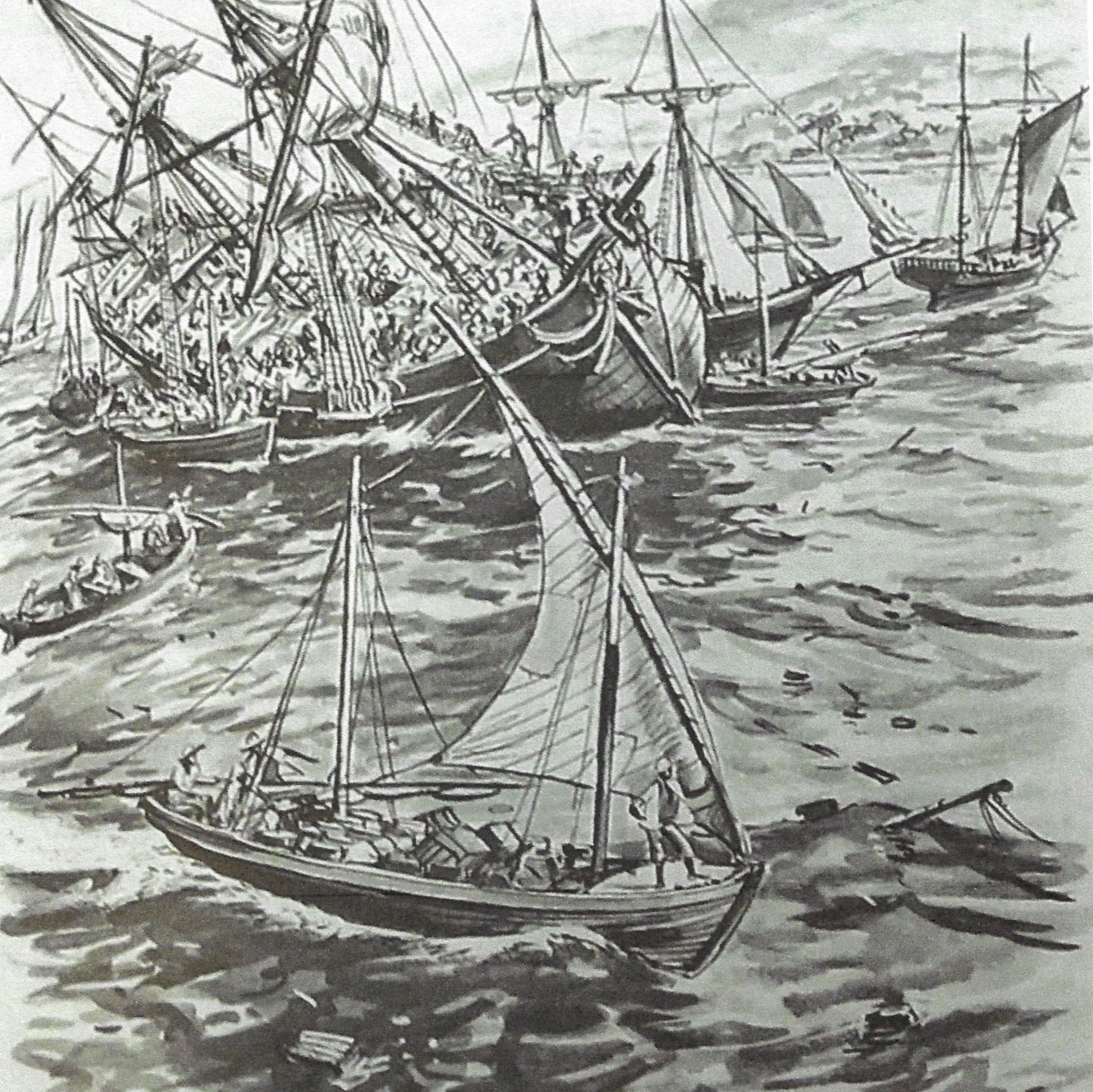

Caribbean free ports had been established in the 17th century to accommodate trade between Spain’s American colonies and Holland, England and France that was illegal under existing Spanish mercantile law. The Spanish government had forbidden foreign trade in its colonies, despite the fact that they desperately needed manufactured goods that only other nations could supply.

In 1766, the English government established free ports on Jamaica and Dominica after the example of Dutch ports on St. Eustatius and Curaçao that had always been open to international trade.

Similar free ports were later established on Granada, New Providence, and Bermuda. Nassau itself was an official free port from 1792 to 1822, when the old mercantile protection system was eliminated.

The first “free ports” were confined to trade and tariff considerations but when manufacturing became equally important in the 19th century, other regulation-free zones were introduced. Such economic enclaves were out of fashion in the mid-20th century (although the tax-exempt industries introduced in Puerto Rico after 1948 could be a successful example), but the handful still in existence may have inspired Wallace Groves.

Stafford Sands & Governor Daniel Knox

Groves turned to perhaps the only Bahamian who had the influence and breadth of vision to help make his grand plan a reality – Stafford Sands. Sands had worked effectively for economic success in the Bahamas through tourism and offshore banking even as he feathered his own nest.

He saw the benefit to the nation in what Groves proposed and was able to scope out a workable plan around the difficult questions of Bahamian taxation and jobs for indigenous workers that was then presented to the Bahamian and British governments.

Fortunately, the governor of the colony, Daniel Knox, the 6th Earl of Ranfurly, also saw the merit of the proposal and secured the necessary support of the British Colonial Office, becoming one of Groves’ most outspoken supporters. Ranfurly acted as intermediary to the Bahamian legislature and working together they brought about passage of the “Hawksbill Creek, Grand Bahama (Deep Water Harbour and Industrial Area) Act.”

The Initial Hawksbill Creek Agreement

Today tourism and vacation home development in the Lucaya district may be seen as the primary result of Freeport’s success, but those features were not part of the original plan. What Groves proposed, and the initial Hawksbill Creek Agreement specified, was the creation of an industrial complex and little more. The Act specified that the “Grand Bahama Port Authority,” incorporated on August 3, 1955 by Groves, under his and his wife’s sole ownership, could lease with an option to buy if the conditions of the Agreement were met, 50,000 acres of Crown land in addition to 80 acres already acquired from private owners, with another 1,420 acres to be bought from other owners.

The acquisition was contingent on the construction of a deep-water harbor and turning basin in three years.

Shipping access required a dredged undersea channel 200 feet wide and 30 feet deep at mean low water, with an additional channel in the creek itself of the same width with a minimum depth of 27 feet. The turning basin included the channel which with further dredging would provide a turning radius of 600 feet. Bordering the harbor there was to be a 600-foot long wharf in Hawksbill Creek and an apron for vehicular traffic 10 feet wide along the harbor side. The property was intended for the new industrial development, “the Port Project,” would be adjacent to Hawksbill Creek and extended three miles east. All of this was the Port Authority’s responsibility and was to be paid for by the corporation.

Enticing Investors with Tax Incentives

The Port Authority also had to recruit firms and investment for the designated industrial development. To help entice investors into an unproven location, the Bahamian government allowed several vital tax incentives.

There would be no real estate taxes, personal property taxes, or income and earning taxes for a period of 30 years after August 5, 1955. After that, rates were guaranteed to be no greater than elsewhere in the Bahamas. In addition, for the 99-year life of the Agreement there would be no government duties or taxes on imports (exempting consumable supplies), no export taxes on things made or imported by the Port Authority and its licensees, and no stamp taxes on funds remitted out of the Bahamas.

These exemptions were and are, having been extended in the first instance, major inducements for investment.

Port Authority Investments

In addition to the harbor and industrial area, the Port Authority agreed to invest in much needed support facilities to create a viable community for future owners, employees and their families:

- Schools that the Port Authority would operate and maintain to a standard equal to those provided on other “Out Islands” by the Bahamas Board of Education.

- Medical facilities including a dispensary, X-ray equipment and hospital facilities (with at least four beds to begin with) staffed by a qualified medical practitioner and a qualified trained nurse to match similar services provided for “Out Islands”. Facilities would be expanded as the population increased.

- Free office space and living accommodations for government officials, and reimbursement of the government for any expense involved (plus 25%) above what the island’s tax revenue would cover.

- Provide and maintain all necessary utilities such as electricity, gas, water, telephone and sewerage disposal systems.

- Insure that all construction met Bahamian standard codes, including those of a future airport if one were built.

If these stipulations were not met, or the harbor not completed in the three-year window, the agreement could be terminated and the Crown land leases would revert to the government. The project would be wound up under the Arbitration Act of 1950 of the United Kingdom.

The Harbour Project

Harbour specifications were completed as required by shipping tycoon Daniel K. Ludwig’s “Bahama Shipyards, Ltd.” by mid-1958. They were extended even further by the time the Port was officially inaugurated in November 1959.

Excavation was a tremendous task, even for someone with Ludwig’s resources, costing £2 million, for which his company was given 2,389 acres of Port Authority property on which to build a shipyard. Dredging was done by the Seahaven, a dredger with an eight-foot cutting head believed to be the largest in the world at the time. The Seahaven was brought south from Wilmington, Delaware to penetrate layer upon layer of limestone rock at the site of the proposed harbour. Even with the powerful dredge, the flint hard bottom of Hawksbill Creek proved to be a major challenge. The cutting head quickly dug through the first ten feet of limestone, but then fragments of the drill-head were tossed up together with the cascading limestone. The rock bottom stalled the project for months until this could be overcome.

Eventually, as much as three to five thousand cubic yards per day were removed, and the by-product was utilized in building Freeport’s roads. The major contractor was the Marine Construction Company, a Savannah-based firm owned by Barney Diamond.

Trying to Imagine the Future

Recruitment of firms for the Port Area was disappointing at first, as the rough undeveloped landscape made hard to imagine what the future might be.

It was a chicken and the egg problem – to attract people to the island, there needed to be sufficient modern amenities and residential development to support the community of employees who would work for the new firms, yet it was these firms that were needed to create that very development.

When the first potential investors came to see the project, primitive conditions raised doubts about the willingness of their employees to move into what was then a frontier settlement. There were no hotel accommodations for visiting families, or shopping plazas, theatres, golf courses, and restaurants. As the Bahamian Review noted in looking back from 1975, the response of the investors was, “We’ll come back and take another look when you’ve got something more to show us.”

Charles Hayward & Other Visionary Investors

One investor was not discouraged by the existing conditions. Charles Hayward, who had been introduced to Wallace Groves by Lord Ranfurly in 1956, stepped forward in July 1959 after Groves chose to accept partners in investment to buy 25% of the shares in the Port Authority for £1 million ($2,800,000).

Hayward was the chairman of the Firth Cleveland group of companies that manufactured British steel and agricultural machinery with operations in the Netherlands, West Germany, South Africa and Australia. His yacht, the Halimede, was among the first large vessels to enter the newly completed harbour even before the docking facilities were ready, so that two bulldozers had to be positioned on either side of the vessel to secure her at anchor.

In 1959, he sent his son Jack to Freeport to represent the family interests, a move that proved tremendously important for the future history of the Port Authority. Another investor was Allen & Company, a New York investment firm that specialized in corporate buyouts. Partners Charles and Herbert Allen were old Wall Street friends of Wallace Groves, who had been in the same business in the 1930s. They created a consortium that bought a not-quite 25% share in the Port Authority for about £1 million, as well.

New Momentum

Having built the harbour and fulfilled the other Hawksbill Creek Agreement conditions by August 1958, the Port Authority was able to buy the original leased Crown lands – an actual 49,894.19 acres – at £1 an acre, a pound then being worth $2.81 American.

Yet even before that, Groves had approached the Bahamian government in April to acquire an additional 40,000 acres at the same price on which to locate new facilities, services and residences. This increase in property involved a Supplemental Agreement to the original 1955 agreement that was signed on July 11, 1960, with the proviso that the Port Authority fund further development to the cost of £1 million within 10 years. The Port Authority had spent twice that amount in development of the Port Area by July 1960, so the Authority was able to exercise its option to buy what turned out to be 88,402 acres. That brought the Port Authority’s Crown land acquisition to a total of 138,296.19 acres, stretching now to 500 feet east of Gold Rock Creek. It was almost 230 of the island’s entire 530 square miles.

There were now a few shops, warehouses and a mess hall and barracks for harbour workers at the harbour, plus a commissary supplied by an old US frigate, the Western Queen, when weather allowed passage from Florida.

Tourism as the Chief Economic Asset

The 1960 Supplementary Agreement was subject to several additional stipulations, chief of which was the construction of a "first-class deluxe hotel accommodation" with a minimum of 200 rooms by the end of December 1963.

Stafford Sands had been Chairman of the Bahamas Development Board since 1950, and having identified tourism as the chief economic asset of the colony, he worked tirelessly to provide the infrastructure of golf courses, nightclubs and hotels that made the Bahamas a world-renowned elite leisure destination in the mid-20th century.

In July 1954, he sponsored a "Hotels Encouragement Act" that gave hotel builders and owners who expanded their existing facilities tax relief incentives similar to those included in the Hawksbill Creek Agreement.

New Benefits for Bahamians

The new agreement also clarified the Port Authority’s obligations, showing how conditions and expectations had changed in the intervening five years.

Now that the Port Authority plan had become a reality, the Bahamas government required the Port Authority to specifically provide free education for all children between the ages of six and 14 living in the Port area, free medical services for the Bahamian Police Force and also for indigent families across the entire island.

It greatly increased the list of approved businesses beyond the original industries to include such things as banking, stockbroking, housing developments, and “owning, constructing, operating and maintaining hotels, boarding houses, clubs … apartment houses, restaurants, marinas, yacht basins and places of entertainment, sport, amusement or cultural activity.”18

A New Name - Freeport

The Port Authority had been accorded the right to name its new possession, and Wallace and Georgette Groves chose “Freeport.” Despite an occasional setback, the new community was now on track to become a reality.

Creating a Community

Building the harbour and industrial area had been the most pressing objective of the Port Authority in meeting the demands of the Hawksbill Creek Agreement but creating a community infrastructure was an equally essential priority. Wallace Groves moved ahead to ensure that Freeport would benefit from the best of contemporary community design. He engaged Jan Porel with whom he had worked at Pine Ridge to undertake the layout of the future metropolis. Porel was an experienced urban designer, as Groves recalled in a 1980 interview:

“You asked me a question as to the planning of the Freeport area, known as the Port area in the Hawksbill Creek Agreement. Actually, I was very fortunate in obtaining the services of a Mr. Jan Porel, a very unusual and experienced person of the highest intelligence and ability. I met Mr. Porel some years prior in the construction of some three thousand houses for the Glen Martin plant in Baltimore, Md. of which he later became Executive Vice President, and Mr. Porel was so highly regarded by American engineers that he was selected by the Government to build the Manhattan project of the first atomic energy plant and he was given carte blanche authority to secure the best engineering talent available in American with a crash program to build the city with[in] 18 months [of the] first atomic bomb. In fact, he was so successful that it is now Oak Ridge, and he completed the job in about a year, I believe. Thereafter, Mr. Porel was made Engineer in Charge, selected by the United States Government and the various allied governments to be in charge of the engineering and development of military facilities in North Africa, including ports, airfields and all military installations. This, of course, was a terrific job. He had just about completed this job when I was able to engage his services in the engineering and planning of Freeport.”

Jan Porel’s Plan

Jan Porel laid out the original grid pattern for downtown Freeport designed around the north-south Mall dual carriageway, and planned the water supply system that still serves the community.

He also built a home near the harbour adjacent to the Groves’ initial Grand Bahama residence, called the “pink house” from its colored stucco, that became known for the same reason, the “green house.”

Porel’s associate Douglas Silvera initiated work on a new airport that began with a 600-foot dirt runway (soon extended to 2,000 feet) where a sheet laid on the ground signaled a request to land to pick up passengers. The first permanent air terminal was in place by 1959.

Urban Planner Peter Barratt

Unfortunately, Porel died before his work was completed, so the Port Authority brought in Harland Bartholomew and Associates, which sent urban planner Peter Barratt to Grand Bahama. The Port Authority was so pleased with Barratt’s work that they hired him away from the American firm.

He was not only instrumental in drawing up the eventual plans for Freeport/Lucaya, but became Grand Bahama’s foremost chronicler of the island’s history.

City Planning from Cornell University

The planning process also involved a study by the students of the City Planning Department of Cornell University. Published in October 1960 as Freeport & Lucayan Town, the oversized planning study was not officially adopted but it did become, as Peter Barratt notes, the “virtual master plan for Freeport.”

Although several major proposals such as the creation of an oceanside convention center connected with a yacht basin for Freeport itself, or a community college in Lucaya were not implemented (yet), the rationale for division between the industrial and residential communities was accepted.

“From the outset, it was plain that the antagonistic interests of a port-oriented industrial centre and a tourist supported resort city were almost irreconcilable; and in the final scheme, this conflict was resolved by creating two separate complexes – a port city of 50,000 persons and a resort city of 87,000 persons (including tourists). … in the larger city, the bulk of the waterfront is reserved for tourist activities with public access provided to beaches at strategic points but between the industrial area and the sea the whole strip is set aside for the public use of the inhabitants of the port town. … The existing city retains the name of Freeport and the new resort was dubbed Lucayan Town.”19

It was only the fact that the industrial sector failed to grow as large as was hoped that resulted in the far greater extent of the tourism and residential area that characterizes Freeport/Lucaya today.

18 Report of the Royal Commission appointed on the Recommendation of the Bahamas Government to Review the Hawksbill Creek Agreement. HMSO, 1971, vol. II, “Appendices”, p. 38.

19 Freeport & Lucayan Town, Grand Bahama Island, Ithaca NY: Cornell University, 1960, p. 37.