Natural History

Caves and Caverns of Grand Bahama

"Grand Bahama is hollow—we have seen her insides!"

The archipelago of the Bahamas sits on submerged carbonate platforms which have been accumulating since the Cretaceous period, and perhaps as early as the Jurassic period. The total thickness of the limestone under the Great Bahama Bank is over 4.5 kilometres (2.8 miles).[1] As the limestone was deposited in shallow water, the massive platform is estimated to have subsided under its own weight at a rate of roughly 2 inches per 1,000 years.

The Bahama Banks were dry land during past ice ages, when sea level was as much as 120 meters (390 feet) lower than at present. The land mass of the Bahamas today represents only a small fraction of their prehistoric extent. When exposed to the atmosphere, the limestone was subjected to chemical weathering that created the caves and sinkholes common to the karst terrain of the land mass, resulting in structures like blue holes.

Jacques Cousteau remarked that the islands were formed like a limestone sponge. Because of this "sponge-like" structure, it has long been known that "ocean holes" – water connected underground to the sea – are common.

Limestone = Caves and Caverns

The Bahamas islands are made up primarily of limestone and, where there's limestone, there are usually caves and caverns, too.

A "cave" is any opening in the ground that's large enough that some portion of it will not receive direct sunlight. "Caverns" are a specific type of cave, naturally formed in soluble rock like limestone. This only applies to dry caves and caverns.

In diving the cavern is the first room at the entrance, where daylight is still visible, anything beyond the day light is defined as cave. Other parameters also define the boundaries of an underwater cavern such as depth and distance from the open air, but the main one is the presence or lack of light. The complex tunnels of Ben’s are cave not cavern.

Limestone easily dissolves in water. Limestone in the Bahamas contain many open cavities, ranging from thin cracks to large caverns. Many of the larger cavities are lined with pure calcite (calcium carbonate) crystals deposited by the ground water in its percolation route.

Caves found throughout the Bahamas are anchialine caves with an inland surface opening having possible subsurface connections to the ocean. Entrances to these typically occur with a fresh to brackish water lens overlaying seawater, as is found at Ben’s Cave. Not all caves connect to the ocean, not all caves have a fresh water lens.

The Lucayan Cavern system on Grand Bahama is over 34,443 feet long and is one of the world’s longest underwater caves. Ben’s Cave is one of the entrances to this underground network.

How Caverns Form

When the sea level is below the level of the land, the downward movement of rainwater through the soft limestone of the island carve out spaces that eventually form caves.

Formations Within Caverns

Stalactites, stalagmites and rock curtains can be found in caverns and caves. These rock features are a result of calcium carbonate-rich waters dripping through the ground layers above leaving deposits on ceilings (stalactites) the floors (stalagmites) or walls (curtains). The presence of these features in underwater caverns reveal that at some point in history the area was dry.

Other Formations – Blue Holes

Created during Pleistocene ice ages when sea levels were lowest, blue holes are a large marine cavern or sinkhole formed by erosion in soft limestone which is open to the surface. Though generally circular in shape, blue holes can also be the result of fractures and fissures and present variable entrance shapes. They typically contain tidally influenced water of fresh, salt or a mixture of waters. They extend below sea level for most of their depth and may provide access to submerged cave passages

On Grand Bahama Chimney Blue Hole is a well-known example. Dean’s Hole, found in Clarence Town, Long Island, is 663 feet deep and the second deepest blue hole in the world.

Learn about Lusca, the mythical creature of blue holesBen’s Cave & Lucayan Caverns

Ben’s Cave is named for Ben Rose, the first man to dive the world-renowned cave system in Lucayan National Park on Grand Bahama. Submerged passages extend horizontally from the main cavern for thousands of yards. Stalactites, stalagmites and other rock formations indicate that the cave was once dry.

Due to the delicate nature of the environment, tours in the cavern are only conducted by Bahamas National Trust approved guides.

Cavern History

The cavern was "discovered" by Anglican priest Father Underhill in 1960. Head of the Grand Bahama diocese, he was driving along Grand Bahama Highway near Freetown when his car broke down and he took refuge in a nearby cave. He eventually told his friend, Ben Rose, about his discovery.

Ben and his brother explored the cavern with diving gear and discovered huge limestone ridges, beautiful crystal formations and fossilized coral and shells. Further exploration revealed the cavern known as the "Skylight Room.” The Old Freetown cavern system, Mermaid’s Lair and Owl Hole are several miles apart and do not share entrances nor tunnels.

Indian Remains Discovery

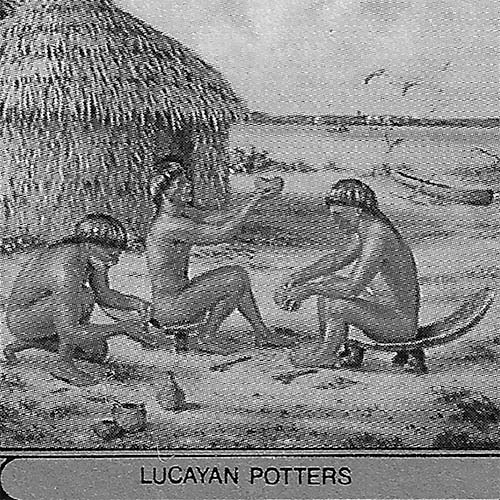

In 1973, Lucayan Indian remains were discovered in Ben’s Cave in about 12 feet of water in what is thought to have been a ritual burial mound.

Dr. Warren Duncan, who was diving with his family, was astonished to discover a human shin bone standing upright in the water. He returned the following weekend, and this time found part of a human skull under a pile of rocks. Due to the flatness of the skull, it was pronounced by the Smithsonian Institution to be definitely Lucayan.

Later, parts of seven or eight more skeletons were discovered, and pulled out of what is now thought to have been a ritual burial mound. Perhaps hoping to find gold ornaments, or else just for the kick of having a human skull to show off at home, various visitors to the cave desecrated this mound before there was a chance of experts examining, photographing or properly measuring the rock on which people had so casually been standing.

One of the skulls found in the burial mound was that of a 12-year-old girl, now named "Lucy." Beside it was a greenish nephrite bead, but were no other artifacts found here.

New Crustacean

Diver Jill Yager PhD, a former teacher at St Paul's School, discovered a new species of crustacean (related to the shrimp) while diving and researching in the cavern system. The totally new crustacean is one inch long, and Yager named it Speleonecies lucayensis, Greek for "Lucayan cave-swimmer.”

Cavern Exploration

With a handful of other keen cave divers, Dennis Williams, an electrical engineer that originally worked at Gold Rock Missile Base, pioneered techniques and developed equipment to explore the Lucayan Cavern system. On his original exploration he used 29,000feet of exploration line, weaving an underground cobweb of surveyed tunnels for six miles. The most recent exploration has been completed by Kewin Lorenzen and Cristina Zenato in 2020.

Williams' diving companions included Gene Melton, an engineer on the U.S. space shuttle at Cape Canaveral, filmmaker Paul Mockler, and marine biologist Jill Yager PhD, of St. Paul's School in Freeport.

Williams and Yager each wore heavy twin air tanks weighing (140 lbs) and a stomach tank (50 lbs.) enabling them to stay submerged for three to four hours on their explorations of the extensive system of submerged caverns.. Other back-up gear weighing some 40 lbs. including survey reels of nylon line.

View underwater tour of Ben's Cave.

These courageous divers made a great contribution to Grand Bahamas history, earning a grant from the American National Science Foundation for research, among other achievements.

Learn more on an underwater tour of Ben's Cave

Learn more about Blue Holes on YouTube and on the Bahamas National Trust website.