Maritime & Aviation

A History of Bahamian Mailboats

1804 to the Present

Thanks to Eric Wiberg for this well-researched history of a critical part of Grand Bahamas history.

Eric Wiberg grew up in Nassau, Bahamas and studied at Boston College, Oxford, Roger Williams (JD) and the University of Rhode Island. He has sailed on 100+ yachts, and operated 21 ships from Singapore. He works for McAllister Towing. His articles have been published in over twenty-five periodicals. A historical blogger, he lives in Norwalk, Connecticut. Learn more at ericwiberg.com

All photos are from the author's collection.

Boats Have Always Been Workhorses

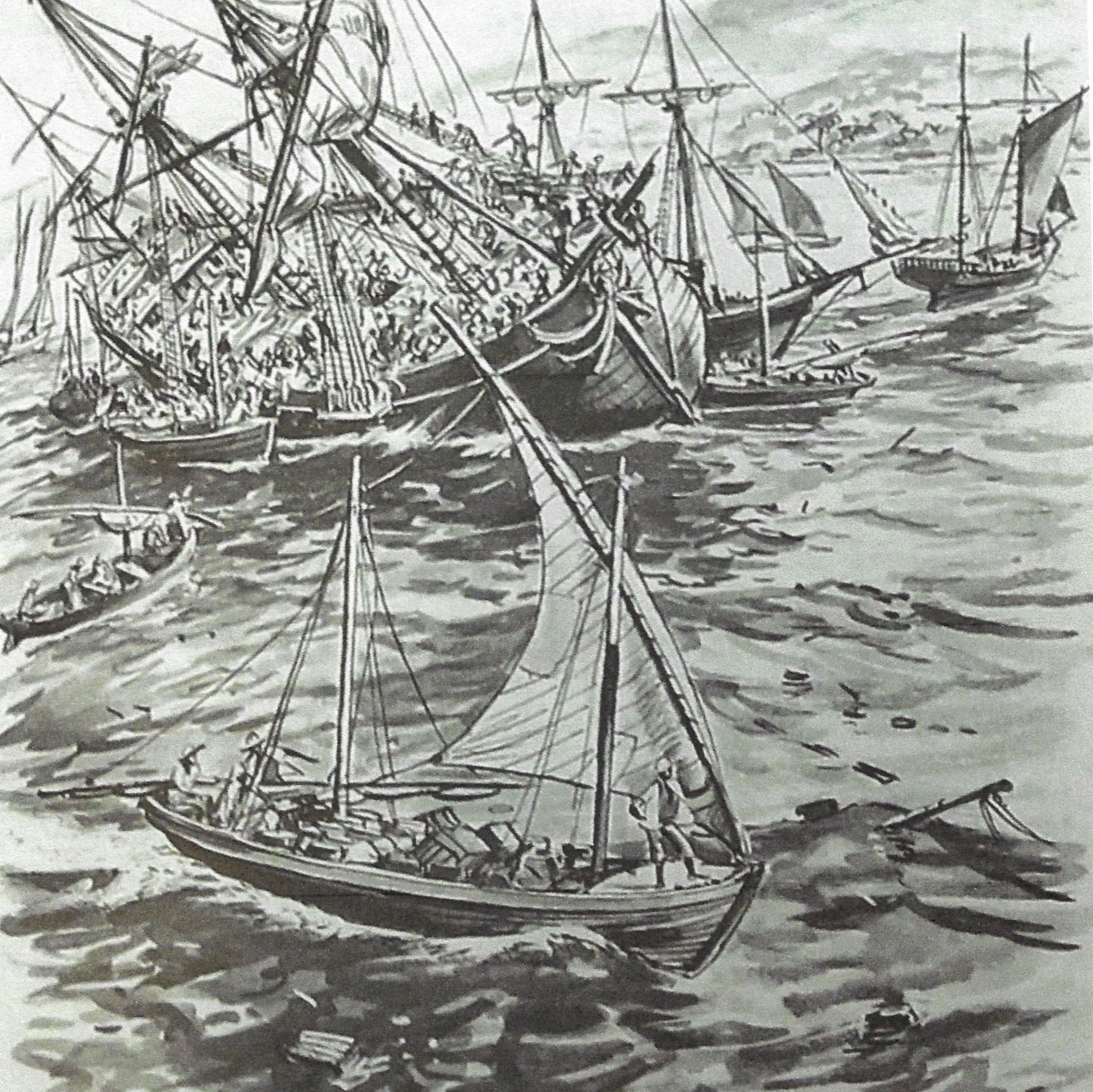

Vessels have been carrying people and goods between the islands of the Bahamas since the time of the Lucayans over 1,000 years ago. Indeed, the Bahamian archipelago – like those of Greece, the Philippines and Indonesia – is reliant on workhorses like its mailboats to ply between the islands carrying everything from people to pincushions, tractors to pickaxes.

Pinning down which years such trade has been government-subsidized proves a challenge, but not an insurmountable one. The quest is as relevant as ever, as presently there are 18 mail boats based at Potter’s Cay in Nassau serving over 45 communities on 14 of the family islands, from Bimini to Inagua.

Origins & Early Years of Mailboats

Though what we know as mailboats will carry everything from church pews to livestock, sodas and beer, passengers, nails, mattresses, vehicles and pretty much everything in between, the focus of early inter-island service was concerned primarily with the mails, as upon that cargo the subsidies relied.

Initially the offices of the Bahamas Gazette served as the post office. Then in 1761 came the “earliest known record of a letter being sent from the Bahamas.” An act for the establishment and regulation of a post office was passed in 1788, followed by the introduction of British postage stamps in 1858 and, just one year later, “the Bahamian post office became independent of London, and issued its own stamps.”

The First Service

As for the origins of the service, one detailed source is the book Bahamas Early Mail Service and Postal Markings by Morris Hoadley Ludington (Alpha Philatelic Printing & Publishing Co., Washington, DC, 1982). He cites the Bahamas Gazette from 1784, the Bahamas Royal Gazette from 1804, and numerous other sources that he read from the originals in the public library, which used to be the goal. He notes that “a vessel called the Nassau Packet sailed a number of times during 1799 between Nassau and Charleston,” but this was not inter-island mail service.

The Mary and Susan

In 1802 Henry Moss of Crooked Island was made Acting Postmaster (p. 8), followed by a Mr. Leitch in Nassau. According to Ludington, “the first mention found in the Bahamas newspapers of Crooked Island and of a Mail Boat being sent from Nassau to meet the Packet there,” was of the Mary and Susan, Captain Fisher, dated Friday, 21 September 1804. The vessel is described as an “armed Government schooner,” as during the Napoleonic Wars “many privateers were active throughout the West Indies” (p. 9).

Soon other vessels – like the John Bull, Captain Fulford, a government felucca, and the schooner Nassau, Captain Gibson, appear, along with the Packet Lord Spencer, on the route to and from Jamaica and England. By 1821 the schooners Dash and Paragon are described as plying the same route, connecting islands within the Bahamas with mail coming from outside the colony.

First Inter-Island Mail Service

In a description of mailboat services dated 5 June 1832 Smyth relates to Goodrich that mail packets came “from England and America through the Bahama Islands using Crooked Island as the chief mailing station.” This was extended to Kingston, Jamaica, and was referred to as intra-island mail service. Truly inter-island mail service is believed to have begun with the 35-foot-long schooner Dart, which was enlarged at its midships twice over its career.

Built about 1867 in Harbour Island, it was owned by John Saunders Harris of that island. One of its captains was William James Harris, born 1848. The boat served Harbour Island, Spanish Wells and Eleuthera from Nassau for over 50 years until about 1922 when it was lost in a hurricane. Accommodation aboard was segregated. Michael Craton and Dr. Gail Saunders, in their seminal work Islanders in the Stream, Volume II, write about Abaco that “sailboats had been replaced by government-subsidized motor mail boat services to most other islands by 1929.”

25 Mail Vessels by 1849

Ludington lists 25 mail vessels plying the inter-island routes of the Bahamas between 1849 and 1885. Chronologically, these were the Palestine, Experiment, Union, President, Electric, Eugene, Georgina, Amelia Ann, Brothers, Mary Jane, Jane, Arabella, Quick, Jimmie, Admired, Dart, Cicero, Charlton, Rebecca, Osborne, Argosy and Attic. By 1849 the following Bahamian ports were being served by mail on a regular basis: East end of Eleuthera, Port Howe, San Salvador, Little Exuma Harbor, North end of Long Island, Port Nelson, Rum Cay, Sandy Point, Watling’s Island, Great Harbour, Long Island, Long Cay, Crooked Island and Inagua.

"Provide for more frequent Communication…"

In March 1865 the government sought to “provide for more frequent Communication between certain islands of the Bahamas and the Seat of the Government.” This may have been an indirect response to the recommendations of Thomas C. Harvey to the Colonial Secretary, C. R. Nesbitt, in 1858 in which he reported “The great variety of productions in the Bahamas would …if there existed an inter-insular steam communication, become available to all, and the cultivation of the land and development of many valuable resources, would speedily follow the power of obtaining a sure market. At present some cays are, at times, absolutely destitute.”

The resultant act (Inter-Insular Communication, 28 Vic. C. 18) found that the previous act for a single vessel was inadequate. Therefore, the new act empowered the Governor, on the advice of the Executive Council, to “hire by the year, or otherwise, for the service…a good and sufficient vessel and pay therefor the sum of money as the same can, by public tender, be procured for not exceeding in the whole sum of five hundred pounds per annum.” The act was good for five years.

Government Subsidization

In May 1867 (30 Vic. C.18) the government specifically enabled subsidized mail service between Nassau and “the Inhabitants of the districts of Eleuthera, Harbour Island and Abaco.” The government was authorized to procure “fastsailing vessels of not less than 20-tons burthen, each to be employed in the conveyance of fortnightly mails.” The act authorized the procurement of three different vessels and confirms the existence of service to Inagua, instructing the post master in Nassau to “make up mails…as he now makes up and dispatches mails by the mail vessel running between Nassau and Inagua.” The act also sets out a tariff for the carriage of freight and passengers – capping the amounts by law. It even governs luggage. The receipts were to go into the public treasury.

There were nine ports covered under this act: Gregory Town, Governor’s Harbour, Tarpum Bay, Rock Sound, Spanish Wells, Dunmore Town (Harbour Island), Cherokee Sound, Great Harbour and Green Turtle Cay Abaco.

Mailboats in the 20th Century

Within a few decades there were acts passed to fill in the gaps between Inagua to the far south and Abaco to the north. For example, “Act (No. 7 of 1907) establish[ed] an Inter-Insular Mail Service in the Bahamas. It empower[ed] the Governor in Council to establish a Mail Service between Nassau and the Out Islands, and to cause contracts to be made for this purpose.”

This 1907 act was further amended and expanded by “An Act to Establish an Improved Inter-Insular Mail Service” passed in August 1948. Through it, the “Governor establish[ed] mail service between Nassau and the Out Islands.” Its geographic scope is broad, as it covers trade “between one Out Island and another Out Island and between settlements in any Out Island district.” It also states that the service may be performed by vessels propelled by sail, steam or “other mechanical power,” such as motors.

The act is granular in its coverage, making allowance for the “sufficient supply of life-saving apparatus and boats, the employment of a competent master and crew, over-crowding, cabin accommodation” and so on. It also calls for the periodic examination of mail vessels and their life-saving equipment. The list of island groups covered is extensive, from Inagua and Crooked Island to the Biminis. There are over 50 communities listed – 10 in Andros alone. The prescribed tonnage of the vessels ranges from 20 to 150 – the largest for the longest routes and only 20 tons for the comparatively short passages from Nassau to the Current in Eleuthera. The act includes specific costs to carry items ranging from “half firkins and kegs, jars and demi-johns” to “tierces, hogsheads, and other vessels not exceeding thirty gallons.” It includes “Madeira, horseflesh wood, yellow wood and other timber…. Potatoes, yams and other roots… mares, mules, and cattle, lignum vitae and braziletto [wood]….”

The Mailboat Act Evolves

The next overhaul of the Mailboat Act, as it is known less formally, came in 1966, and again the rules were tweaked in 1974 and 1987. Interestingly, mailboat owners with dual roles in government such as Sir Roland Symonette and Sir George Roberts had hands in shaping legislation.

Then in 1995 and 1996 the “Rates for Carriage of Freight” rules were amended again, basically updated and modernized to keep the investors, entrepreneurs and mailboat owners in their livelihood. The latest version on the Official Website of the Government of the Bahamas is from October 1966 – an amended version of the 1948 act. On the site is the agreement that mailboat owners can enter into with the government. This requires the service provider to subject their official logs twice yearly for inspection and to keep up the ship’s Registration Certificate, Business License, and Inter Insular Mail Shipping Rates. If the vessel and its officers and crew and the service provided are deemed not up to government standard, then the government can revoke the license and, with it, the agreement.

Mailboats are Here to Stay

In March 2008 it was reported that the government had signed a three-year contract with mailboat owners and operators “in response to complaints by mail boat owners and operators that the tariff does not take into account that the cost of doing business has escalated and the cost of fuel has also increased exponentially.” The tariff they amended was drafted in 1996.

In a contemporary article from The Eleutheran, the Honorable Sidney Collie wrote that “My Ministry is aware and very concerned about the price of diesel fuel and the impact that it is having on the mail boat industry and the economy as a whole.” The article continued, observing that “the Family Island residents depend heavily on the mail boat for transportation of goods and other essential services.”

Serving Remote Communities Today

In short, the Mailboat Act and its amendments remain vibrant and, to some degree, flexible documents, enabling mailboat operators to continue to serve remote communities with affordable, reliable access to the capital across the decades and centuries.

It is noteworthy that government subsidy of the mails has enabled at least one mariner and entrepreneur, Captain Ernest Dean of Sandy Point, Abaco, to make his career, motivated at first by the need to obtain regular supplies of milk for his infant children. Starting in 1949 when he constructed the mailboat Captain Dean in Sandy Point by hand, without electricity (it took over two years to build), he went on to commission and ply six vessels under the same name and numerous others owned and operated by his family before his recent death. His life, boats and career are chronicled in the book Island Captain (White Sound Press, 1997).

As Vibrant and Essential As Ever

In March 2015 the Minister of Transport and Aviation announced that the government had allocated $3.1 million towards wreck removal, refurbishment, expansion of warehousing, repair of the causeway and installation of bathrooms at Potter’s Cay. Despite attrition like the sinking of the Andros mailboat Lady D in July 2014, whose wreck still clutters otherwise useable dock frontage, it would appear that the inter-island freight and mail service can, with help, remain as vibrant a part of the Bahamian islands’ fabric as it has been for at least 200 years.

After more than 160 years of service, the picturesque arrival and departure of a mailboat, with its accompanying cacophony of activity, still elicits excitement and celebration and is embedded in the culture of the islands.

Watch the Lady Rosalind II Mailboat that provides passenger service, imports all goods to the islands, and transports live animals from conch to goats and agricultural products to market in Nassau. Mailboats provide a critical lifeline to many islands of the Bahamas.

Mailboats and their transit between islands even appears in the music of the Bahamas – Watch and listen to “Stop That Mailboat” performed by the Brilanders to a Calypso beat.

In the Seattle Times: “Island-hopping the Bahamas by Mailboat”

Click here to view Portraits of Mailboats