History of the Port Authority

Creation of the Grand Bahama Port Authority

Groves consulted with his old friend Stafford Sands and the two of them came up with the plan for what would become the Grand Bahama Port Authority (GBPA).

Groves’ initial concept was for a standard free port completely free of import and export duties, but Sands observed that as the Bahamian government depended heavily on import duties for income, this would not be acceptable. They developed a modified plan for a largely tax and regulation (and, initially, trade union-free) exempt commercial enclave where trade and manufacturing could compete with nearby Caribbean and U. S. ports, but which would still collect duties on anything not directly connected with building and conducting businesses.

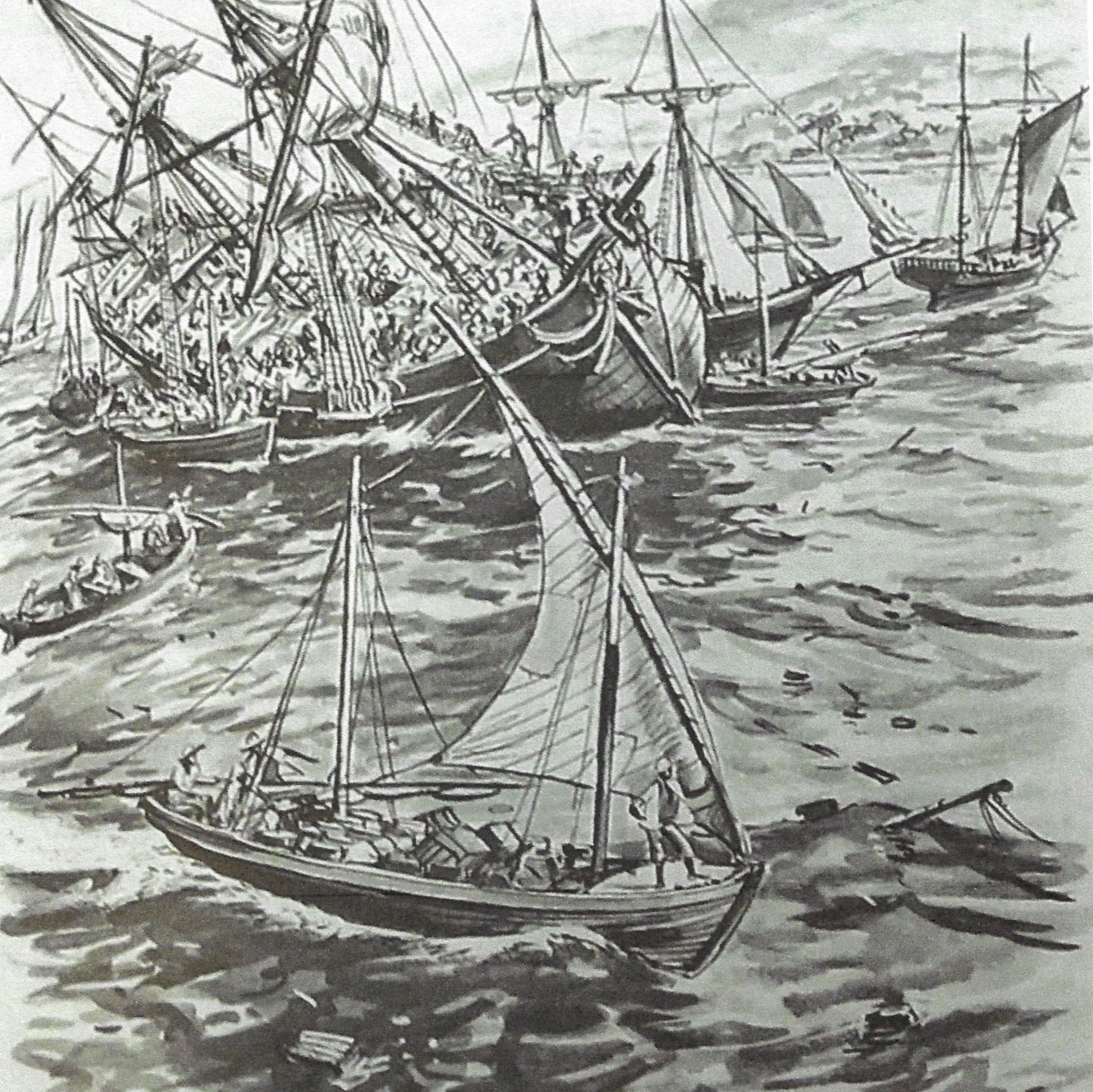

The port and industrial zone would be used for excise-free transshipment of goods (especially oil) and for the processing of products for export—any items that were distributed within the Bahamas would automatically become taxable. They initiated talks with the Bahamian Government in 1953, which led to the drafting and signing of the Hawksbill Creek Agreement on 4 August 1955.

The Hawksbill Creek Agreement

This remarkable contract between the Bahamian colonial government and a private corporation wholly owned by the Groves family was negotiated at a time when the old colonial structure was still in place.

Once details were hammered out between the British Crown (represented by Acting Governor Gardner-Brown) on behalf of the Bahamian government and the Grand Bahama Port Authority (represented by Wallace Groves—with Stafford Sands in the background), the process was authorized by an Act of the Bahamian legislature, the “Hawksbill Creek, Grand Bahama (Deep Water Harbour and Industrial Area) Act” on June 22, and the Agreement was signed.

It should be noted that the legislative act was separate from the contract, and did not in itself create the Port Authority.

The Act itself, which incorporates the Hawksbill Creek Agreement, can be consulted on the Bahamian Government website.

Special Conditions

Under the conditions of the Hawksbill Creek Agreement, the Crown agreed to “grant conditional purchase leases” to the Port Authority for 50 thousand acres of Crown Land surrounding Hawksbill Creek on Grand Bahama and to “grant a conditional purchase lease” to the Port Authority of the sea bed near and underlying Hawksbill Creek.

In addition, the Port Authority agreed to purchase 80 acres from private owners and had the option (which was accomplished with some difficulty) to buy an additional 1,420 acres of privately held land in the area. The Crown lands were priced at a minimal £1 per acre; the pound then being about $2.80 US. Within three years and six months, the Port Authority was to provide the colonial government with a detailed survey of the land in question, which turned out to involve 49,894.19 acres of Crown land along with the private 1,420 acres.

To make the Port Authority enclave economically viable and attractive to overseas investors, the Bahamian government agreed to exempt the Port Authority, its residents and employees from all taxes on real or personal property, capital gains, income in or outside the colony, excise or customs duties for specified imports and all exports out of the colony for a period of 30 years. After the 30-year period, the freedom from excise duties and the other provisions of the Agreement would continue for another 69 years (a standard British leasehold period being 99 years), and any new taxes would be no more than they were elsewhere in the Bahamas.

In return, the Port Authority agreed to, within three years, create a new harbor and channel capable of handling large vessels 200 feet in length with a minimum depth of 30 feet at mean low water from the sea to the mouth of Hawksbill Creek, and within Hawksbill Creek, dredge a channel not less than 200 feet in width with a minimum depth of 27 feet, and also create a turning basin for the ships with a turning radius of not less than 600 feet wide. In addition, they were to construct a wharf at least 600 feet long with a ten-foot wide “apron” to allow vehicles to access the ships.

The Promise of Local Industry

Further, the Port Authority was to promote and encourage the establishment of factories and industries (the rationale for the extensive acreage) to benefit the Bahamian economy and provide employment for the colony’s citizens. It was suggested that industries which could best exploit the natural resources of the island be particularly sought out (although the limestone and pine were fairly limited in their usefulness). No mention was made or implied concerning the salubrious climate and aesthetic beauty of the landscape—the Bahamas had those resources elsewhere, and it was industry (and agriculture) that was seriously lacking.

It is clear that the primary intent of the special deal was industrial development, made possible by the impressive new harbor. Grand Bahama had not attracted earlier settlement or development precisely because there had been no viable harbor on the southern side of the island. However, the harbor alone was not enough to insure development. The services, infrastructure and amenities necessary for modern life, such as roads, electricity, water, supermarkets, restaurants, schools, churches, hospitals, banks, places of recreation and housing, had to be made available for the employees, officials and their families who would work in the new community before many could be convinced to move there.

It was a tremendous task to create a contemporary community from scratch on the island’s pine barrens and limestone landscape, especially as everything had to be imported.

Support Facilities, Maintenance & More

The Agreement included a number of stipulations concerning the construction of necessary support facilities as well as the continued maintenance of the port. The Port Authority was to build and maintain schools, provide medical services and utilities such as power and water, supply rent-free living and office accommodations for any officers and employees of the Bahamian government that the government might station in the Port Area, and reimburse the government for all expenses involved, including salaries (and 25% for overhead).

They also agreed to allow “free access at all reasonable times to the Port Area and to any works being constructed in connection with the Port Project and/or the Port Area Development.” It also stipulated that the Port Authority was not subject to the usual governmental permitting and licensing procedures for construction and business establishment.

Duty-Free or Not?

As Stafford Sands had expected, the Agreement went into considerable detail on the question of which goods could be imported free of duties and which could not.

In general, the former included everything that was to be used in the operation of businesses (“manufacturing and administrative supplies”) in the Port Authority area, including materials used to construct the new industrial base and the community infrastructure. Anything intended for or re-allocated to personal use (“consumable stores”) was excluded, on the same principal that allows U.S. corporations to claim tax deductions for expenses, materials and supplies used in the actual operation of a business but nothing more.

The tax exemption was extended to individual proprietors and businesses licensed to operate within the Port Authority area. To help insure that each of the licensed businesses was reputable and beneficial to the overall goals of the Agreement, the Port Authority was required to notify the Bahamian government (through the Colonial Secretary) of each individual or corporation issued a license within 30 days of granting the license.

Employment Issues

One point that would prove contentious later was the right the Port Authority and its licensees were given in authority to employ foreign nationals (particularly “key, trained, and/or skilled personnel” but also manual workers) to work on Grand Bahama. This was even though the government reserved the authority to refuse admission to “personally undesirable” individuals and to expel such people it felt were a problem at the Port Authority’s expense.

There was really no alternative for truly highly-qualified positions, for which there were few if any viable candidates among the Bahamian population. However, there seems to have been considerable hiring of Haitian and other unskilled alien laborers where there might have been potential openings for native Bahamians.

While the Agreement recognized that finding people with the requisite skills to manage and operate the new businesses would necessitate recruitment abroad, this was balanced by a concern that the Port Authority not become an uncontrolled alien intrusion within the colony.

It was stipulated that “no workmen or labourers recruited outside of the colony by the Port Authority or by any licensee shall be contracted for any longer period than three years” with the right of renewal, presumably with the intent of insuring that the Port Authority would benefit the local population and the colony’s internal economy to the greatest extent possible.

The Port Authority also agreed to make a positive effort to “employ Bahamian-born persons within the Port Area, provided such Bahamian-born persons are available and are willing to work at competitive wages or salaries” and, in a nation where higher education, professional training and technical expertise were generally unavailable, to “use their best endeavours to train Bahamian-born persons to fill positions of employment within the Port Area.”

Such training was not always forthcoming.

Roads & Bridges

Another clause that caused some resentment stipulated that:

“all roads and bridges constructed by the Port Authority … within the Port Area shall be deemed to be private roads and bridges and that the Port Authority shall have the absolute right to exclude any person and vehicle (other than an officer or employee or vehicle of the Government) from using the same, and to exclude any person … from the Port Area or any part thereof without assigning any reason therefore.”

Although this is no more than the commonly accepted right of an owner of private property, such as the buildings and grounds of an industrial plant, the very extent of the Port Authority and the fact it effectively cut the island in two, made the possible restriction on the local population from traveling freely on their own island a ticklish issue.

Clause #28

Lastly, there was this clause that guaranteed that the conditions of the Hawksbill Creek Agreement would not be arbitrarily rescinded by the government at some later date, and provided recourse to arbitration under British law.

This was an important consideration, as what a government gives it can also take away, and without some security against future impositions, overseas investors might be reluctant to make expensive commitments that could later be swept away, as was then occurring in former colonies.

Giveaway or Not?

Was this a colossal “giveaway?” No. For one thing, the purchase of the land was conditional—the Bahamas would not lose in the end if the venture failed and the property was returned to the Crown through reversion, and the Agreement was for a finite period of 99 years. Consider the risk involved. How many grand schemes of this sort have sunk without a trace in the islands? There was no guarantee that Groves could pull it off, and if he didn’t, the land would revert to the government after three years, and there might even be a harbor and some roads left behind—all to the general good.

It was a chance for the Bahamas to obtain through private international investment facilities, jobs and benefits that were far beyond the ability of the government to provide.

Private Ownership: A Revolution or Not?

Secondly, was the concept of a self-contained community in which almost all of the infrastructure and utilities were privately owned and administered a revolutionary one?

Again, no—the example of the old-fashioned mill town, for example, provided a precedent. Earlier in the century there were about 200 such “company towns” in New England, where everything from schools, churches, post offices, stores, workers’ houses to utilities such as electricity, water and roads were built, maintained and owned by a corporation—often, as in the example of “Talcottville” in Vernon, Connecticut, by the Talcott’s family owned firm. While the mill town was legally within the jurisdiction of (and paid taxes to) a public municipality, the property was privately owned and operated just as a single factory building might be.

Such "towns" were fast disappearing in New England as the textile trade that supported them moved south after World War I, but the concept was quite familiar to men of Wallace Groves’ generation.